Did you know, it is estimated 50% of the adult male Caucasian population will develop male pattern baldness, also known as androgenic alopecia (Leliefeld et al)?

Pattern baldness is associated with excessive hormonal stimulation of the skin, by the hormone testosterone and its derivatives, leading to a reduced rate of hair growth and shrinkage of the components of the skin that generate the hair shafts. The result is a distinctive pattern of hair loss on the top and sides of the head (Severi et al).

Finasteride, a medicine that can restore hair regrowth, is often prescribed to men who develop alopecia. While finasteride can be beneficial in restoring hair regrowth, it has been associated with some serious side effects, particularly after drug withdrawal, so called Post Finasteride Syndrome. Symptoms experienced by men after withdrawal of finasteride include sexual and cognitive dysfunction leading to depression and changes in mood (Leliefeld et al).

Let’s take a closer look at how a treatment for hair loss may lead to mental depression.

Finasteride is an enzyme inhibitor. Enzymes are specialised proteins that increase or decrease metabolic reactions in the body, essentially controlling the rate at which these reactions occur. Finasteride blocks the enzyme responsible for the conversion of the hormone testosterone (T) to its more active form, dihydrotestosterone (DHT) (Yamana et al). Blocking this conversion allows the skin to reinstate hair regrowth, hence reversing the alopecia (Severi et al).

Most enzymes work in teams. The enzyme team responsible for the conversion of T to DHT is called 5α reductase or reductase for short, and it has three team members - reductase 1, 2 and 3. Finasteride is most associated with inhibiting the actions of reductase 2 (Leliefeld et al). However, work carried out by Yamana et al, has shown that finasteride has similar affinity for reductase 3. Interestingly, this group also showed that reductase 3 was much more active in the brain, when compared to reductase 2 and was more highly expressed in the brain compared to other organs, suggesting finasteride’s inhibiting effect could be more impactful on the brain.

Like all body parts, the skin and its components that manufacture the hair shafts are made up of cells, the individual building blocks that provide structural integrity to all organs. For DHT to have its effect on the skin, it must bind to a particular receptor in these cells. Think of DHT as the key and the receptor it binds to as the keyhole, together they allow a locked door to be unlocked. The receptors that bind DHT are called androgen receptors (ARs). When prescribed to men for alopecia, finasteride is often administered for months or even years. When an enzyme inhibitor like finasteride is administered for that long, it will lead to a reduction in hormone concentrations, in this case DHT and T (Saim Baig et al). Finasteride treatment in men has been shown to reduce the concentration of DHT in blood by up to 70% (Roberts et al).

This leads to the desired clinical effect, hair regrowth, but the body asks itself an important question. If we have lost the keys, maybe we don’t need the locks? The body responds to a decrease in T and DHT, by reducing the number of ARs (Saim Baig et al). Assessing the effect of finasteride administration on the kidney in a mouse model, it was demonstrated there was a reduction in ARs. Also, androgen deprivation therapy (like finasteride administration) for prostate cancer has been associated with downregulation of ARs (Liu et al).

Dart et al demonstrated that brain AR activity was highly specific to small areas of the brain in male mice, while Cara et al reported that AR activity in the mouse was highest in areas of the brain such as the amygdala, a brain region commonly associated with depression related pathology in men (Pandya et al).

But aren’t ARs only involved in hair growth? ARs are important receptors in many parts of the body, including the brain. When activated by their constituent hormones, such as DHT, they can act on the cells control centre (nucleus), to increase or decrease its activity. They are also important for controlling actions outside the cell nucleus, especially in the cells lining the blood vessels that supply the brain (Abi-Ghanem et al).

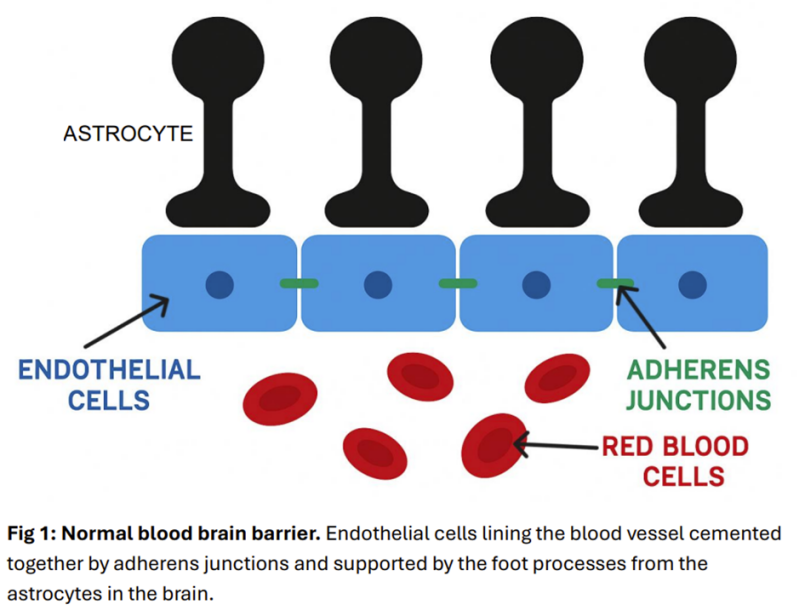

The blood flowing through the body in the general circulation is not allowed to mix directly with the blood supplying the brain. The gatekeeper is a structure called the blood brain barrier (BBB). It is composed of the cells lining the blood vessels (endothelial cells), intimately apposed with specialised brain cells called astrocytes. The gaps between the endothelial cells are cemented together by specialised proteins, called adherens junctions (AJs) (tight junctions (TJs) are also important). Interestingly, AJs control the function of tight junctions (Saim Baig et al). Astrocytes have long octopus like foot processes that overlap these junctions to form an additional layer of reinforcement. The BBB is very selective and will only allow necessary molecules to pass through it (Rhea and Banks) (Fig 1).

Finasteride administration in an animal experimental model caused a change in adherens junctions in epithelial cells of the kidney (Saim Baig et al). Atallah et al, demonstrated in a mouse model that chronic depletion of testosterone led to increased permeability of the blood brain barrier. This BBB leakage was also associated with activation of white blood cells (defence cells) in the brain and an increase in inflammatory signals. Supplementation with testosterone restored BBB selectivity.

While reductase converts T to DHT, it is also involved in the production of other hormones, such as androstenedione (A), which has been shown to reduce inflammation in the endothelial cells lining the blood vessels in the human brain (Zuloaga et al). Reductase enzymes have a higher affinity for androstenedione, when compared to the conversion of T to DHT (Yamana et al). Androstenedione exerts its effect by binding to different receptors, called ERs (estrogen receptors). Therefore, finasteride will also inhibit the production of androstenedione, possibly negating these beneficial anti-inflammatory properties (Yamana et al) in those very cells required to maintain a healthy BBB.

Interestingly, in a tear gland animal model, finasteride administration decreased tear production, which was associated with a decrease in ARs (Li et al) and evidence of inflammation, with white blood cell infiltration observed on microscopic examination of the tear glands (Zhang et al). In another animal model, an increase in white blood cells was observed in the kidneys of finasteride treated rats (Saim Baig et al).

The imbalance of disrupted steroid hormones (T, DHT and A) and decrease in their receptors (ARs and ERs) may be associated with altering the junctional proteins, such as AJs and TJs cementing the endothelial cells of the BBB and hence, inducing inflammation in the brain (Fig 2).

Brain endothelial cells are well endowed with AJs, which are composed of proteins, including β catenin, acting as strong anchors between cells. AJs are considered key signalling elements involved in barrier regulation of brain endothelial cells. Βeta catenin has been identified as a crucial component of an important signalling pathway (WNT), which is believed to be the main inducer of barrier properties of the BBB (Devraj et al). In prostate cancer cells, it has been shown that β catenin can interact directly with ARs activating genes promoting cell proliferation, providing a direct link between AR and AJ interactions (Mitani et al).

Beta catenin is known to be an important co-regulator of AR activity (Wang et al). The level of β catenin activity in the nucleus of cells needs to be carefully monitored, but it is clear, it should never be too high or persist for long periods (Valenta et al). In the presence of reduced DHT and ARs, β catenin concentrations in the cell may become altered, driving excessive and possibly prolonged periods of β catenin induced nuclear activity. Could this in turn alter the β catenin pool that is necessary to maintain healthy adherens junctions and a healthy BBB?

In summary:

-

Finasteride has similar activity against reductase 3, when compared to reductase 2

-

However, reductase 3 has greater activity in the brain compared to other organs

-

Finasteride reduces hormone (A, DHT and T) and hormone receptor (AR and ER) activity

-

In health, AR activity is greatest in certain areas of the brain such as the amygdala, an area known to be important in depression related pathology in man

-

ARs are important in regulating the activity of the cell nucleus, increasing and decreasing protein production and are very important in maintaining the integrity of the cells lining blood vessels in the brain, an important component of the BBB

-

Finasteride administration has been shown to change adherens junctions in mice and one of the effects of finasteride -reduction of testosterone, has been shown to increase BBB leakage and induce inflammation in the same species

-

Finasteride can also reduce androstenedione, a hormone known to have anti-inflammatory properties protecting the endothelial cells lining the blood vessels in the brain

-

Therefore, an imbalance in steroid hormones and ARs could alter adherens junctions and BBB functionality

-

As reductase 3 has been shown to be more active in the brain, its inhibition may lead to prolonged reduction in AR expression, even after drug withdrawal. Prolonged reduction in AR activity in brain cells may lead to WNT/β catenin signalled alterations in the AJs, inducing BBB leakage that may predispose to inflammation and mental deterioration, such as changes in mood and depression.

While losing one’s hair can certainly lead to a decrease in self-esteem and make one self-conscious, it might be best to accept it as part of the aging process or consider other treatment options, such as hair transplantation, to avoid the possible serious side effects with medical intervention associated with 5α-reductase inhibitors. It is important that medical professionals inform patients of these potentially serious side effects when prescribing finasteride for pattern alopecia.

References:

Leliefeld HHJ et al. (2023). The post-finasteride syndrome: possible etiological mechanisms and symptoms. International Journal of Impotence. Research volume 37, pages 414–42.

Severi G et al. (2003) Androgenetic alopecia in men aged 40-69 years: prevalence and risk factors. Br J Dermatology. 149(6):1207-13

Yamana K et al. (2010) Human type 3 5α-reductase is expressed in peripheral tissues at higher levels than types 1 and 2 and its activity is potently inhibited by finasteride and dutasteride. Hormone Molecular Biology and Clinical Investigation. 2(3): 293-299.

Saim Baig M et al. (2019) Finasteride-Induced Inhibition of 5α-Reductase Type 2 Could Lead to Kidney Damage-Animal, Experimental Study. Int J Environ Res Public Health.16(10):1726.

Roberts JL et al. (1999) Clinical dose ranging studies with finasteride, a type 2 5alpha-reductase inhibitor in men with male pattern hair loss. J Am Acad Dermatol. Oct;41(4):555-63.

Liu et al. (2012) Prolonged androgen deprivation leads to downregulation of androgen receptor and prostate-specific membrane antigen in prostate cancer cells. Int J Oncol. 2012 Dec;41(6):2087-92.

Dart DA et al. (2024) Analysis of androgen receptor expression and activity in the mouse brain. Scientific Reports. Volume 14, Article number: 11115.

Cara AL et al. (2021) Distribution of androgen receptor mRNA in the prepubertal male and female mouse brain. J Neuroendocrinol. Dec;33(12):e13063

Pandya M et al. (2012) Where in the brain is depression? Curr Psychiatry Rep. Dec;14 (6):634-42.

Abi-Ghanem C et al. (2020) Androgens’ effects on cerebrovascular function in health and disease. Biol Sex Differ. Jun 30;11:35.

Elizabeth M. Rhea and William A. Banks. (2019) Role of the Blood-Brain Barrier in Central Nervous System Insulin Resistance. Front. Neurosci. Volume 13.

Atallah A et al. (2017). Chronic depletion of gonadal testosterone leads to blood–brain barrier dysfunction and inflammation in male mice. Journal of Cerebral Blood Flow & Metabolism. Vol. 37(9) 3161–3175.

Zuloaga K L et al. (2012). The androgen metabolite, 5α-androstane-3β,17β-diol, decreases cytokine-induced cyclooxygenase-2, vascular cell adhesion molecule-1 expression, and P-glycoprotein expression in male human brain microvascular endothelial cells. Endocrinology. Dec;153(12):5949-60.

Li K et al. (2017). Evaluation of a novel dry eye model induced by oral administration of finasteride. Mol Med Rep. Dec;16(6):8763-8770.

Zhang C et al. (2016) The Effect of the Aqueous Extract of Bidens Pilosa L. on Androgen Deficiency Dry Eye in Rats. Cell Physiol Biochem. 39(1):266-77.

Devraj K et al. (2025). Regulation of the blood-brain barrier function by peripheral cues in health and disease. Metabolic Brain Disease 40:61.

Mitani T et al (2012) Coordinated action of Hypoxia-Inducible Factor-1 and catenin in androgen receptor signaling. J Biol Chem. Sep 28;287(40):33594-606.

Wang G et al. (2008) Crosstalk between the Androgen Receptor and β-Catenin in Castrate Resistant Prostate Cancer. Cancer Res. December 1; 68(23): 9918–9927.

Valenta T et al. (2012) The many faces and functions of β-catenin. The EMBO Journal 31, 2714–2736.

Add comment

Comments

This was really interesting, I didnt know much about PFS before but I feel I have a better understanding of it now. I wonder whether developing a drug that selectively inhibits reductase 2 while leaving reductase 3 intact would be able to treat alopecia without causing the symptoms seen in PFS. Could this maintain androgen receptor activity in the brain to keep the amygdala functioning normally and prevent the blood brain barrier leakage, while still reducing hair loss?

Really interesting blog, it makes me wonder whether a truly local, brain-sparing formulation could prevent the neurological risks while still helping with hair loss and without affecting androgen signaling in the brain. Has there been any research into this?

What an eye-opening read — I honestly never realised how something as “simple” as a hair-loss medication could have such a complicated ripple effect in the brain. The link you made between finasteride, androgen receptors, and the stability of the blood–brain barrier is especially striking, because it ties together so many different systems we normally think of as separate. The part about reductase 3 being more active in the brain really surprised me too — it makes the neurological side effects make a lot more sense.

One thing I’m wondering is whether any studies have looked at whether these BBB changes are reversible after stopping finasteride, or if the AR downregulation can persist long-term. Do you think the brain can fully “reset,” or could some of these signalling changes linger even after hormone levels return to normal?