The history of the miracle known as finasteride, and how it gained such widespread popularity?

The story of finasteride began in the 1980s, when scientists at Merck, a multinational life science company, made a groundbreaking discovery: an azasteroid compound, i.e., a steroid derivative, now known as Finasteride, could be a potent inhibitor of the 5 Alpha Reductase Enzyme Type 2 Isozyme. Three types of 5 Alpha Reductase Isozymes exist, but only type 2 is competitively inhibited with minor inhibition of type 3 by Finasteride. (Zito, et al., 2024). This was a miracle drug for patients who suffer from benign Prostatic hyperplasia (BPH), a condition whereby enlargement of the prostate gland can cause impairment of the urethra, leading to bladder obstruction (Kirby & Gilling, 2011). DHT was identified as the main culprit in the proliferation of prostate cells, which leads to BPH.

Furthermore, a new and fresh indication was soon to be on the horizon for those suffering from Male Pattern hair loss (MPHL), also known as androgenetic alopecia. Androgens, particularly DHT, were found to be the primary cause of hair follicle miniaturization in the scalp, attributed to increased levels of scalp DHT. Due to the previous research that led to the development of finasteride for BPH, it was also theorized that a 5 Alpha Reductase inhibitor may help reduce hair loss, as finasteride prevents the conversion of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone; it has been shown to result in clinical improvement in the progression of MPHL. (Kaufman, et al., 1998).

What is finasteride? How does it work?

Finasteride is a molecule known as a 5 Alpha Reductase Enzyme inhibitor, which was first indicated for use in BPH and later in MPHL or Androgenetic Alopecia. It is synthesized in the laboratory using various chemical and crystallization techniques to bring about the Active Pharmaceutical properties that inhibit 5 Alpha Reductase. The mechanism of action by which finasteride works is by blocking the 5-alpha reductase-mediated conversion of testosterone to Dihydrotestosterone (DHT) (Diokno, et al., 2024), as shown in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. Representation of the conversion of Testosterone to Dihydrotestosterone mediated by 5 Alpha Reductase Enzyme. Inhibition of 5 Alpha Reductase Enzyme by finasteride, leading to inhibition of DHT formation. (Structures drawn using Procreate, Structures adapted from NIH Database.

Finasteride treatment is a standard prescription in modern-day practice, which doesn’t require a specialist or consultant physician to prescribe. A prescription can be obtained simply from a General Practitioner or through some online prescribing services. An American Hair Loss Association article published on June 18, 2024, reported a 200% increase in the prescription of finasteride over the last seven years. (Anand, 2024). The rise in prescriptions may be due to a surge of young to middle-aged men trying to halt their increasing hair loss. With that said, is finasteride an entirely harmless medication, or is there an ugly side to the drug?

A Closer Look at Finasteride Side Effects: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly.

Outside of the positive “side effects” of finasteride treatment, such as the shrinkage of prostate tissue in BPH or halting hair loss, or even restoration of the hair follicles, adverse side effects have been established with the use of finasteride, as outlined in the Proscar Package leaflet that is found on the HPRA website, typical side effects include impotence, decreased libido, ejaculation issues. (Merck Sharp & Dohme Ltd, 2024). That is only the bad side effects associated with finasteride treatment, and there are much uglier outcomes when using the drug, as anecdotally told by many thousands of patients throughout the years. While the side effects to be mentioned are also listed on the package leaflet for finasteride, their occurrence or frequency isn’t estimated, thus leading to a 'Not Known' occurrence. These side effects are most likely due to post-marketing surveillance and reports submitted to the manufacturer of finasteride. The side effects are as follows: Ejaculatory issues, which do not resolve post cessation of medication, Infertility, low-quality sperm, decreased libido post cessation of medication, Anxiety, Depression, and suicidal ideation. Post cessation = Post Finasteride Syndrome.

Introduction to Post-Finasteride Syndrome: clinically relevant or myth?

Post-Finasteride Syndrome (PFS) is a medically hypothesized condition that isn’t a clinically recognized diagnosis as of 2025 (Trüeb, et al., 2025). It first shot to notoriety in 2011 when a journal article was published on the use of finasteride in men suffering from male pattern hair loss (MPHL) and an associated link to adverse sexual side effects. The study sought to define types and duration of symptoms relating to sexual dysfunction, such as low libido, erectile dysfunction, and ejaculation issues. (Irwig & Kolukula, 2011). Before the 2011 article by Irwig & Kolukula, several studies had consistently demonstrated that the use of finasteride has an excellent tolerance and safety profile, with any side effects associated with treatment being rare and reversible (Pereira & Coelho, 2020).

The authors Irwig & Kolukula began to investigate the potential link between the use of finasteride and sexual dysfunction, which was founded on two clinical trials, which were funded by the pharmaceutical companies Merck and GlaxoSmithKline (GSK), which produced Finasteride (Propecia) and Dutasteride (Avodart), respectively. In the Merck trial, it was observed that the incidence of symptoms of sexual dysfunction was greater than that compared to the placebo, as shown in Table 1. In the GSK trial, it was observed that more trial participants encountered symptoms of sexual dysfunction in one category (Decreased Libido) when compared to the placebo group, as shown in Table 1.

(Table 1.) Incidence of Sexual Side Effects: Finasteride vs Dutasteride vs Placebo. 1First Year Data

To date there is a divide in the medical community when it comes to the theory of finasteride causing sexual and psychological symptoms.

Proposed mechanism by which finasteride causes psychological and sexual long-term side effects known as Post Finasteride Syndrome.

To date, there hasn’t been any clear evidence or reasoning as to why patients experience symptoms that are consistent with the title of post-finasteride syndrome. There is, unfortunately, no known evidence based treatment for PFS (Traish, 2020). There is also no understanding of why only some men on finasteride treatment experience PFS and others do not. Potentially, a cascade of compounding factors could lead to PFS, such as dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis (HPA), epigenetic changes, pre-existing psychiatric pathology, Androgen Receptor Sensitivity, and duration and dosage of finasteride treatment. As PFS is a multifactorial issue with numerous symptoms, many of the above categories may be the cumulative cause of PFS. To classify PFS and propose a suitable hypothesis, PFS will need to be categorized into some of the above categories, and the downstream effects to be analyzed to corroborate the etiology of PFS.

Hypothalamic-Pituitary-Adrenal Axis.

Beginning with the HPA Axis, it has vital importance in psychological homeostasis and controlling glucocorticoid production in response to stressors and biological rhythms. In normal biological function, the HPA axis is activated by the production of corticotropin-releasing hormone (CRH), which originates in the hypothalamus and acts directly on the pituitary gland. This event triggers the release of Adrenocorticotropic Hormone (ACTH) from the pituitary gland and stimulates the adrenal glands to release glucocorticoids. This is the standard operation in healthy individuals as seen in Figure 2. However, evidence from animal studies suggests that the reduction of testosterone to dihydrotestosterone is a crucial process required for inhibiting the HPA Axis response to stress. Inhibiting 5 Alpha Reductase in mouse models leads to an inverse relationship between DHT levels and HPA activation, demonstrating that while androgen deprivation had no impact on corticosterone levels, it did, however, show increases in ACTH levels, which were associated with an enhanced HPA Axis response to stress conditions. (Zuloaga, et al., 2024).

Figure 2. Showing normal HPA Axis function in healthy individuals. Created using Biorender.

An increase in ACTH over time would lead to Cushing's syndrome-like presentations that could be considered pseudo-Cushing syndrome, which includes symptomology such as reduced fertility, low sex drive, erectile dysfunction, and depression (X, 2017 ). A dysregulated HPA Axis over time can have many downstream effects, which contribute to plenty of the chronic conditions seen in PFS, such as mood disorders and poor stress response(Ring, 2025). Furthermore, dysregulation of the HPA Axis has been linked to microbiome dysbiosis; in other words, chronic HPA axis dysregulation impacts the gut-brain axis, leading to an abundance of physiological and psychological symptoms. It is thought that inflammatory/immune proteins, known as Interleukins (ILs), such as IL-1 and IL-6, have been identified as biomarkers in individuals with HPA dysfunction (Misiak, et al., 2020).

Epigenetic expression.

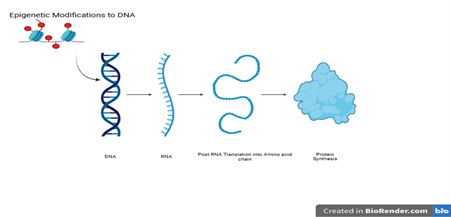

Epigenetics is a behavioral and environmental function that is directly related to genetic expression, meaning that your environment and behavior may dictate which genes are expressed and which are silenced. Plenty of known exposures and diseases can hijack epigenetics, such as smoking, cancer, pregnancy, nutrition, and infections (Centers For Disease Control, 2025). Not all epigenetic functions are bad, such as exercise and healthy diet practices, which promote the expression or silencing of genes that are involved in cellular pathways. With that said, let's take a look at when epigenetics doesn’t work in our favor.

Figure 3. Showing epigenetic modifications to DNA leading to protein synthesis. Created in Biorender

Every day, the drugs we take to treat conditions may also impact the way our genes are expressed through the mechanism of epigenetics. In the case of finasteride treatment, studies suggest that, as is known, 5 Alpha Reductase Enzyme inhibition has a downstream effect on neurosteroid biosynthesis, which can impair critical regulatory functions and modulation of neurotransmitter receptors, such as gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA) (Traish, 2018). Biological outcomes that are undesirable can be explained by epigenetic changes in gene expression due to finasteride treatment, such as the upregulation of androgen receptors (AR) and increased post-translational modification (PTM)of Proteins, which may increase the chance of developing mood-related disorders such as depression, anxiety, and suicidal thinking. Epigenetic susceptibility of individuals on finasteride treatment may play a key role in the development of PFS.

Psychological History.

Studies conducted to investigate the link between PFS and Finasteride treatment have often been thwarted by an individual's pre-existing psychiatric history. It was observed that greater than 50% of individuals who took part in the study reported they had a psychiatric diagnosis prior to taking finasteride. Additional research is required to rule out pre-existing mental illnesses as a compounding factor for the diagnosis of PFS (Ganzer & Jacobs, 2016). This may, in fact, be tied into the idea of the nocebo effect, as mental illness is very nuanced; there are cases where people may be more susceptible to symptoms and beliefs based on the prior disclosure of adverse events (AEs) and symptoms associated with medical treatment. These psychological phenomena may elicit negative or worsening outcomes when compared to groups which do not have pre-existing knowledge of AEs or symptoms associated with treatment (Colloca & Miller, 2011).

Combined hypothesis.

As finasteride directly works by lowering DHT levels through the inhibition of 5 Alpha Reductase, it has an inhibitory effect on systemic levels of 5 Alpha Reductase types 2 and 3. With that said, this condition may very well begin with the psychological history of the patient, but to propose a mechanism by which Finasteride causes PFS, a genetic and endocrinological approach must be taken to explain this cascade. Beginning with the dysregulation of the HPA Axis, it is observed when DHT levels are reduced there is an inverse relationship to CRH and ACTH. As levels of ACTH rise, the HPA axis cannot be inhibited due to low levels of DHT, meaning physiologically a patient would have increased cortisol that, over time, will disrupt endocrinological feedback loops and cause neurochemical and steroidal imbalances which may induce physiological and psychological symptoms.

The potential reason that post-cessation of finasteride, individuals’ symptoms do not improve could be due to 1. The initial treatment using finasteride and the dysregulation of the HPA axis & 2. The epigenetic switches are made as the patient becomes more endocrinologically out of control. When hormone signaling is impaired, this may cause a reprogramming of gene expression, which can impact various aspects of a person’s physiology and psychology, such as impairment of post-translational modifications, neurotransmitter signaling, and modulation of serotonergic reception and other crucial neurotransmitters.

The combination of HPA Axis dysregulation and epigenetic changes may create a positive feedback loop, rendering the cessation of finasteride ineffective. Using gene therapy may yield excellent results in the future for patients suffering from PFS. If a singular gene can be identified or multiple genes, there may be hope that using a genetic therapy, such as Adeno-Associated Virus (AAV) vector technology, which delivers the appropriate genetic corrections to an individual’s defective gene (s), can be effective. This is all thanks to a virus vector which is altered by removing pre-existing viral genetic material and replacing it with recombinant genetics that target defects. If a gene of interest were to be identified, SRD5A may be a good candidate. As SRD5A is involved in N-Linked glycosylation and the folding of proteins in order to function correctly, if epigenetic changes occur that impacts the expression of SRD5A leading to protein folding issues this may impact biosynthesis of crucial regulatory functions that could cause the symptoms observed in Post Finasteride Syndrome.

The current state of affairs.

On April 22, 2025, the FDA updated the regulated products section for finasteride, stating that it had become aware of adverse events related to the use of compounded finasteride topical treatments. The Adverse events reported through the FDA Adverse Event Reporting System (FAERS) show consistent events when compared to those of the oral finasteride products, such as decreased Libido, anxiety, depression, and erectile dysfunction, to name a few (FDA, 2025). This may shed new light on the potential risks associated with finasteride treatment and could help further the conversation surrounding PFS. To date, an increasing number of physicians are becoming more aware of the potential risks associated with starting a 5 Alpha Reductase inhibitor and hopefully they use further and extensive clinical judgement when prescribing finasteride.

References

Anand, 2024. Booming Demand: U.S. Sees 200% Surge in Finasteride Prescriptions Over 7 Years. [Online]

Available at: https://www.americanhairloss.org/booming-demand-us-sees-200-surge-in-finasteride-prescriptions-over-7-years/

[Accessed 27 October 2025].

Centers For Disease Control, 2025. Epigenetics, Health, and Disease. [Online]

Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/genomics-and-health/epigenetics/index.html#cdc_health_safety_special_topic_overview-what-it-is

[Accessed 31 October 2025].

Colloca, L. & Miller, F., 2011. The nocebo effect and its relevance for clinical practice. Psychosom Med, 73(7), pp. 598-603.

Diokno, A. C., Kunta, A. & Bowen, R., 2024. Testosterone and 5 Alpha Reductase Inhibitor (5ARI) in Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia (BPH): A historical perspective. Continence, 12(101711), p. 2.

FDA, 2025. FDA alerts health care providers, compounders and consumers of potential risks associated with compounded topical finasteride products. [Online]

Available at: https://www.fda.gov/drugs/human-drug-compounding/fda-alerts-health-care-providers-compounders-and-consumers-potential-risks-associated-compounded

[Accessed 26 October 2025].

Ganzer, C. & Jacobs, A., 2016. Emotional Consequences of Finasteride: Fool’s Gold. American Journal of Men’s Health, 12(1), pp. 90-95.

Irwig, M. S. & Kolukula, S., 2011. Persistent Sexual Side Effects of Finasteride for Male Pattern Hair Loss. The Journal of Sexual Medicine, 8(6), p. 1747–1753.

Kaufman, K. et al., 1998. Finasteride in the treatment of men with androgenetic alopecia. Journal of the American Academy of Dermatology, 39(4), p. 578–589.

Kirby, R. S. & Gilling, P. J., 2011. Fast Facts: Benign Prostatic Hyperplasia. [Online]

Available at: https://ebookcentral-proquest-com.glucksman.idm.oclc.org/lib/univlime-ebooks/reader.action?docID=800613&ppg=3&c=UERG

[Accessed 22 October 2025].

Merck Sharp & Dohme Ltd, 2024. Package leaflet: Information for the user PROSCAR® 5 mg film-coated tablets finasteride , Dublin: Organon.

Misiak, B. et al., 2020. Depression and suicide risk associated with 5α-reductase inhibitors. Pharmacology & Therapeutics, Volume 102.

Pereira, A. & Coelho, T., 2020. Post-finasteride syndrome. Anais Brasileiros de Dermatologia, 95(3), pp. 271-277.

Ring, M., 2025. An Integrative Approach to HPA Axis Dysfunction: From Recognition to Recovery. The American Journal of Medicine,, 138(10), pp. 1451 - 1463.

Traish, A., 2018. The Post-finasteride Syndrome: Clinical Manifestation of Drug-Induced Epigenetics Due to Endocrine Disruption. Current Sexual Health Reports,, 10(2), pp. 151-160.

Traish, A. M., 2020. Post-finasteride syndrome: a surmountable challenge for clinicians. Fertility and Sterility, 113(1), pp. 21-50.

Trüeb, R. M. et al., 2025. Comment on current investigations into the postfinasteride syndrome. International Journal of Trichology, Volume 8, p. 245.

X, B., 2017 . Effects of Chronic ACTH Excess on Human Adrenal Cortex. Journal: Frontiers in Endocrinology, Volume 8, p. 43.

Zito, P., Bistas, K., Patel, P. & Syed, K., 2024. Finasteride. In: StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing.

Zuloaga, D. et al., 2024. Dihydrotestosterone regulation of stress-related behaviors in mice exposed to subchronic variable stress. Endocrinology, 65(10), p. 10.

Add comment

Comments

This was an interesting insight into many things that could be at play in PFS. I am interested in the treatment you proposed as it was also something I considered.

A study conducted by Melcangi et al found after analysing methylation patterns on the genes that encode for the 5α-reductase enzyme, the SRD5A2 promoter gene was more frequently methylated in the CSF of PFS patients compared to controls. As SRD5A2 encodes for the type II isoenzyme, it is suggested that the methylation-induced silencing of SRD5A2 in the CNS could lead to persistent reductions in neuroactive steroids leading to symptoms of depression.

This could be a possible target for the viral vector gene therapy. The vector could deliver the genes encoding for TET enzymes. The enzymes could possibly then alter the methylation pattern on the gene and reverse methylation induced silencing. Is this something you explored and do you have any other information on alternative targets or gene therapies?

I like the focus on a specific gene therapy option.

I find the last part of the first paragraph on the HPA axis and the first part in the ‘combined hypothesis section’ hard to follow and how it specifically relates to mental depression symptoms – it states:

“Inhibiting 5 Alpha Reductase in mouse models leads to an inverse relationship between DHT levels and HPA activation” this therefore means 5 alpha reductase inhibition, which leads to a decrease in DHT, will activate the HPA and therefore increase cortisol/corticosterone.

The next part of the sentence reads “demonstrating that while androgen deprivation had no impact on corticosterone levels” – Androgen deprivation therapy will lower DHT, which according to the first part of the sentence, should increase cortisol.

And finally – “it did, however, show increases in ACTH levels, which were associated with an enhanced HPA Axis response to stress conditions.” Increased ACTH should lead to increased cortisol/corticosterone? And if the HPA response is enhanced, this would also mean increased cortisol/corticosterone?

Can you help clarify the mechanism?