Try opening PubMed and searching for “chronic traumatic encephalopathy”, you will get 1.502 results. Now, try adding the word “females” to you search bar: 222 results. The discussion almost always revolves around professional athletes: soccer players, football players, boxers. And even though the word “athlete” isn’t gendered, nearly all studies only consider men. What about the other 50% of the population?

One article analysing 50 individuals affected by chronic traumatic encephalopathy included only two women (Fahr et al., 2024). Embarrassing for 2025. Yet FIFA reports confirm that there are currently around 5 million officially registered female soccer players worldwide, and when accounting for unregistered ones, the total number is estimated to exceed 15 million (FIFA, 2023). Now imagine how many women actively participate in other contact sports like boxing, football, and hockey. And still, for decades, research has underestimated the impact that chronic traumatic encephalopathy has on women.

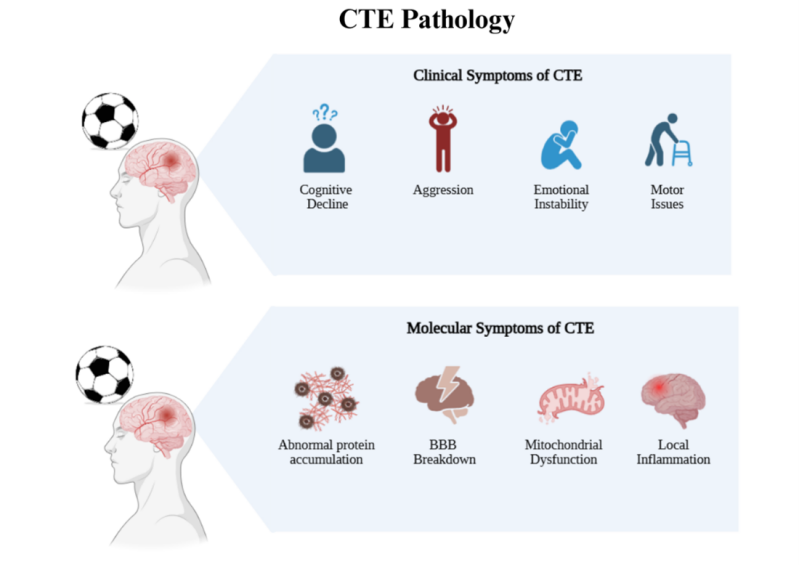

Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) is one of the most common neurodegenerative disorders associated with repeated head injuries (RHIs) in contact sports athletes. The symptoms include memory loss, cognitive decline, behavioural changes such as aggression or impulsivity, mood disturbances, speech and motor impairments and, in advanced stages, dementia (McKee et al., 2016a). Inside the brain, CTE is linked to the buildup of an abnormal form of a protein called tau, mainly in the frontal areas of the brain. Many people with CTE also show a build-up of another protein called amyloid beta and other common signs at a cellular level include damage to the blood-brain-barrier (BBB), problems with the cell’s energy factories (mitochondria), inflammation, and protein tangles that harm neurons (McKee et al., 2016b).

Figure 1: Visual representation of CTE pathology. Created in https://BioRender.com

This disease rises many unresolved questions. First, no diagnostic biomarkers are available for living individuals. Meaning that a conclusive diagnosis can only be made post-mortem (Makhoul et al., 2025). This limitation exists because CTE is very complex. It shares some features with other brain diseases like Alzheimer’s but also has unique traits.

Existing diagnostic approaches focus on cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) marker such as hyperphosphorylated tau, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), and S100β (marker of BBB disruption)(Makhoul et al., 2025). However, the levels of these markers fluctuate over time, being more prominent during the acute inflammatory phase, whereas most patients present clinical symptoms year later, often after retirement, typically around eight years following repeated head trauma (Makhoul et al., 2025).

This delayed onset raises critical questions: why do symptoms emerge so late? Why are cognitive outcomes not routinely monitored throughout athlete’s careers? And why do symptoms worsen even after the acute inflammatory phase has subsided? One possible explanation is that chronic inflammation, rather than being a milder form of the acute response, represents a persistent and maladaptive state. Over time, long-lasting inflammation can damage brain cells. Setting the stage for irreversible neurodegenerative processes that culminate in dementia.

But again, most of the studies conducted for biomarker identification were performed on males. This male-centred research focus is limiting our understanding of the disease, cutting off half of the world population. From the few studies focussing on sport-related concussion outcomes in females and males, it has been shown not only that women report more and worse symptoms, but also that women have higher deficits in neurocognitive performance than males (Fahr et al., 2024). But why? Why do women experience more severe outcomes post CTE?

A potential answer lies in hormone regulation in the brain, specifically the enzyme aromatase and its gene CYP19A1, which converts testosterone into estradiol, a hormone with strong protective and anti-inflammatory properties.

In 2013, Garringer et al. demonstrated that genetic differences in CYP19A1 significantly influence CSF levels of estradiol and testosterone after traumatic brain injury (TBI) (Garringer et al., 2013). Individuals with lower CSF estradiol (with weaker aromatase activity) had higher mortality rates and worse recovery after TBI. Suggesting that estradiol helps calm inflammation and supports brain repair (Garringer et al., 2013).

This insight is particularly relevant to CTE, which results from repeated mild TBIs over time. If aromatase activity is insufficient or dysregulated, the brain’s ability to convert testosterone into neuroprotective estradiol may be compromised. As a result, this could limit the brain’s ability to heal and make it more vulnerable to long-term degeneration.

Moreover, CTE symptoms typically manifest in middle age, a stage of life when aromatase expression and circulating sex hormones levels naturally decline(Gavett et al., 2011, Biegon et al., 2015). This drop further reduces local estradiol availability in the brain, worsening the neuroinflammatory and degenerative processes initiated by earlier injuries. Consequently, diminished aromatase activity may not only hinder recovery after trauma, but also accelerate neurodegeneration later in life, linking hormonal ageing with the delayed onset of CTE pathology. This could help explain why symptoms often appear years after the last injury,

Moreover, estradiol keeps mitochondria healthy and prevents abnormal tau buildup through key cell signalling pathways (Simpkins et al., 2008). Therefore, reduced aromatase-related estradiol synthesis could directly exacerbate the tau accumulation and mitochondrial dysfunction characteristic of CTE.

Differences in aromatase activity may also help explain sex-specific vulnerability. Human studies show that certain CYP19A1 variants are linked to increased Alzheimer’s disease risk in women, implicating estradiol regulation in female cognitive resilience (Huang and Poduslo, 2006). After brain injury, women may exhibit different CNS aromatase responses, influencing local estradiol availability. Since estradiol suppresses pro-inflammatory signalling, deficits in CNS aromatase could make females more sensitive to repetitive trauma-induced inflammation, offering a molecular explanation for why women experience more severe and prolonged CTE-related outcomes.

Figure 2: Timeline illustrating how aromatase and estradiol activity following CTE modulate inflammation and recovery outcomes. Created in https://BioRender.com

Ultimately, CTE may be more than a tauopathy. It could represent a neuroendocrine-inflammatory disorder, where hormonal resilience, mediated by CNS aromatase, shapes delayed symptoms emergence and sex-specific progression. Future research should consider genetic differences in CYP19A1 and track hormone-related factors in both men and women over time to better predict long-term brain outcomes.

In conclusion, this article does not aim to offer definitive solutions to the many unanswered question surrounding CTE, but rather to highlight a critical gap in current research: the lack of sex-specific approaches. Biological differences between males and females are not peripheral details. They are central to understand disease mechanism. Considering factors such as hormonal regulation, aromatase activity, and neuroinflammatory responses may provide the missing link in explaining CTE’s variability and delayed onset. Only by studying both sexes equally we can move closer to uncover the true complexity of this unique neurodegenerative disorder.

References

BIEGON, A., ALEXOFF, D. L., KIM, S. W., LOGAN, J., PARETO, D., SCHLYER, D., WANG, G. J. & FOWLER, J. S. 2015. Aromatase imaging with [N-methyl-11C]vorozole PET in healthy men and women. J Nucl Med, 56, 580-5.

FAHR, J., KRAFF, O., DEUSCHL, C. & DODEL, R. 2024. Concussion in Female Athletes of Contact Sports: A Scoping Review. Orthop J Sports Med, 12, 23259671241276447.

FIFA. 2023. WOMEN'S FOOTBALL: Member Associations Survey report 2023 [Online]. FIFA.

GARRINGER, J. A., NIYONKURU, C., MCCULLOUGH, E. H., LOUCKS, T., DIXON, C. E., CONLEY, Y. P., BERGA, S. & WAGNER, A. K. 2013. Impact of aromatase genetic variation on hormone levels and global outcome after severe TBI. J Neurotrauma, 30, 1415-25.

GAVETT, B. E., STERN, R. A. & MCKEE, A. C. 2011. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy: a potential late effect of sport-related concussive and subconcussive head trauma. Clin Sports Med, 30, 179-88, xi.

HUANG, R. & PODUSLO, S. E. 2006. CYP19 haplotypes increase risk for Alzheimer's disease. J Med Genet, 43, e42.

MAKHOUL, J. T., NASR, A. G., QAZI, Z. G., PIPER, B. J., AHMED, A. N. & JAVEED, A. 2025. Neurobiology and Impact of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy in Athletes: A Focused Review. Cureus, 17, e86367.

MCKEE, A. C., ALOSCO, M. L. & HUBER, B. R. 2016a. Repetitive Head Impacts and Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy. Neurosurg Clin N Am, 27, 529-35.

MCKEE, A. C., CAIRNS, N. J., DICKSON, D. W., FOLKERTH, R. D., KEENE, C. D., LITVAN, I., PERL, D. P., STEIN, T. D., VONSATTEL, J. P., STEWART, W., TRIPODIS, Y., CRARY, J. F., BIENIEK, K. F., DAMS-O'CONNOR, K., ALVAREZ, V. E., GORDON, W. A. & GROUP, T. C. 2016b. The first NINDS/NIBIB consensus meeting to define neuropathological criteria for the diagnosis of chronic traumatic encephalopathy. Acta Neuropathol, 131, 75-86.

SIMPKINS, J. W., YANG, S. H., SARKAR, S. N. & PEARCE, V. 2008. Estrogen actions on mitochondria--physiological and pathological implications. Mol Cell Endocrinol, 290, 51-9.

Add comment

Comments

Those statistics you mentioned really stand out. it’s surprising how such a large population of female athletes is still so underrepresented in CTE research. I hadn’t realised the gap was that wide before I done my own blog on this topic. I wonder if some of it might come down to logistical challenges, like smaller professional leagues, fewer long-term studies, or limited access to medical data in women’s sports. Strengthening data collection and creating shared databases across female leagues might help make future research more accessible.

Thanks for pointing that out! There’s definitely still a lot of work to do in CTE research, and the lack of data on the female population makes progress even harder.

That’s why I didn’t want to focus on proposing specific “solutions” to CTE itself, but rather on highlighting the existing sex-based discrepancies.

It would be great to open this discussion with other professionals in the field, for example, strength and conditioning coaches in female contact sports to improve access to data and raise awareness. The more we scale up the research, the closer we get to finding real solutions.

An interesting and badly needed take! — the gender gap in CTE research is honestly shocking when you lay out the numbers the way you did. I had no idea the difference in PubMed results was that extreme until you spelled it out. The link you make between aromatase, declining estradiol, and the delayed onset of symptoms is especially interesting, because it ties together the biology and the lived experiences of female athletes in a way most papers completely overlook.

I’m really curious about one thing: do you think sports organisations (like FIFA or the IOC) should start including hormone profiling or aromatase genotyping as part of long-term concussion monitoring programs? Or would that create more problems than it solves?

Hi Grace, thank you so much for your thoughtful comment!

I do think that incorporating hormone profiling, or even just routine hormonal monitoring ,could eventually become a useful tool for identifying athletes who may be at higher risk of developing CTE, especially as we learn more about how estrogen, aromatase, and neuroinflammation interact over time.

That said, we’re not at the stage where organisations like FIFA or the IOC could implement this responsibly. What we really need first is solid bench research: controlled studies, longitudinal data, and a clearer molecular understanding of how hormonal fluctuations influence CTE vulnerability in female athletes. Once that foundation is built, then it would make sense to expand into preventive strategies within sports organisations, where these injuries actually occur.