Imagine taking a pill to stop hair loss only to find out months later that there are unexpected consequences. For some men this is a reality. Finasteride is a small molecule therapeutic agent and the active ingredient in Propecia, and it is used worldwide to treat hair loss. However, for an unfortunate subset of users the effects last long after the final dose has been taken. They develop Post-Finasteride Syndrome (PFS) which comes with a mix of sexual, mental and physical symptoms -including fatigue, depression, anxiety and ’metal fog’ or emotional numbness. These effects can persist for months or even years after stopping the drug (Irwig, 2012; Ganzer, Jacobs and Iqbal, 2015).

The existence of Post-Finasteride Syndrome is debated within the medical community. Many clinicians acknowledge patient reports of long-lasting symptoms while others argue that the evidence is limited (Kiguradze et al., 2017).

Is it Hormones?

Finasteride works by changing how the body processes testosterone. Normally testosterone gets converted into a stronger form called Dihydrotestosterone (DHT). DHT causes hair follicles to shrink. Finasteride blocks the enzyme responsible for the conversion, so the body does not produce as much DHT (Clark et al., 2004; Drake et al., 1999).

Figure 1: Finasteride mechanism of action. Finasteride blocks enzyme that converts testosterone to DHT- reducing hair loss. -Image created at https://www.biorender.com/

The most common explanation for the symptoms seen in PFS focuses on hormones as changes in DHT levels can affect both libido and mood. However, the problem with this explanation is that for most men affected DHT levels return to normal once the drug has been stopped but the symptoms persist (Clark et al., 2004). So perhaps it isn’t the hormones causing the problems but instead the cells that respond to them.

The cells:

Every cell in the body has an outer layer called the cell membrane and within this layer are organised regions called lipid rafts that are rich in cholesterol and proteins. Lipid rafts help process messages about hormones, energy and mood (Brown and London, 1998; Levental, Grzybek and Simons, 2010). One of the main jobs of lipid rafts is managing calcium signalling. Calcium ions carry small electric charges that trigger nerve impulses, control muscle contractions, and goes to the mitochondria to produce energy inside the cell. Due to the wide variety of roles calcium plays, even a small disturbance in regulation of calcium levels can lead to changes in the brain, muscles and metabolism (Berridge, Bootman and Roderick, 2003; Clapham, 2007; Rizzuto et al., 2012).

When cell communication breaks down:

-

Loss of sexual and vascular function:

Calcium and potassium channels work together in blood vessels to control relaxation. If one of them becomes dysregulated, blood flow does not occur correctly, which can lead to erectile and circulatory issues (Nelson and Quayle, 1995; Ledoux et al., 2006).

-

Brain fog and mood changes:

Nerve cells rely on calcium channels to send messages efficiently. If these channels lose their structure the signalling between neurons becomes weakened (Catterall, 2011). This weakened signalling may explain the brain fog and other similar issues reported by patients with PFS (Irwig, 2012).

-

Chronic Fatigue:

Calcium helps the mitochondria produce energy. If calcium levels drop ATP, a form of energy, production drops and oxidative stress can build up. This would leave the body very tired and reactive (Duchen, 2000; Giorgi et al., 2012).

-

Inflammation:

Microglia are the brains immune cells, and they use calcium to regulate how they respond to stress. If the balance is disturbed the microglia can become chronically active and release inflammatory molecules like TNF-α, and IL-6, which in turn can lead to issues with mood, sleep, energy, anxiety and depression(Norden and Godbout, 2013; Kettenmann et al., 2011; Eyo and Wu, 2013).

Over time these processes feed into each other. The weak signalling, low energy and inflammation could form a loop that leads to symptoms long after finasteride is no longer being used.

A New Hypothesis: The Lipid raft- Calcium signalling Hypothesis

Finasteride may disrupt the structure of lipid rafts leading to dysregulation of calcium signalling.

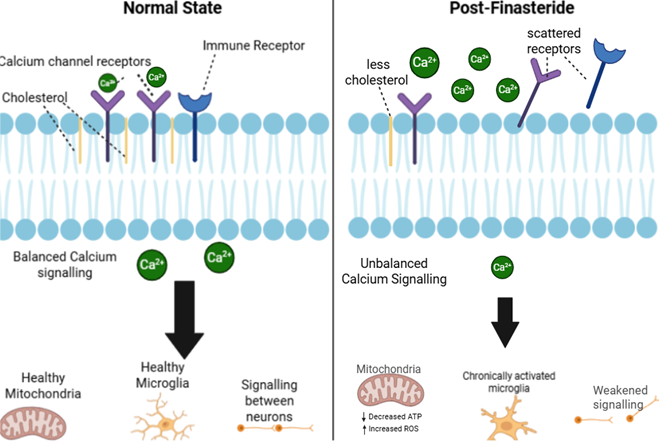

Finasteride works by blocking an enzyme linked to the sterol pathway, this is the same network used to produce cholesterol which is a key component of lipid rafts (Russell and Wilson, 1994; Melcangi and Panzica, 2006). When less cholesterol is available the lipid rafts become unstable. Proteins that depend on the lipid rafts such as calcium channels and immune receptors scatter leading to an effect across multiple systems.

This mechanism could explain why the symptoms of PFS are so long lasting and varied. It links neurological, vascular and immune systems under the one process-Disrupted calcium signalling.

Figure 2: Comparison of normal calcium signalling vs potential calcium signalling in people with PFS. -Image created at https://www.biorender.com/

Testing the theory:

Researchers could explore the hypothesis from several angles by combining cell biology, imaging and molecular analysis.

-

Stem-Cell studies

Patient samples could be reprogrammed into induced pluripotent stem cells and then guided to grow into neurons and microglia (Takahashi et al., 2007). Calcium movement could be observed using fluorescent dyes (Berridge, Bootman and Roderick, 2003). If the PFS cells have weaker calcium signalling compared to control cells it would support the hypothesis that disrupted calcium signalling contributes to symptoms.

-

Membrane mapping

Methods such as mass spectrometry can be used so that the composition of lipid rafts in cells from PFS patients can be compared to healthy cells (Foster, De Hoog and Mann, 2003). If proteins, especially calcium channels and immune receptors, are displaced or absent it would suggest signalling pathways have been damaged. The cholesterol levels in these cells could also be investigated (Simons and Toomre, 2000).

-

Imaging of the brain

Inflammation and glial activation in the brain can be studied using TSPO-PET scans. It is a type of molecular imaging that tracks microglial activity (Zhang et al., 2021). If the scans show higher TSPO binding in brain regions linked to mood and cognition it would demonstrate that the microglia remain in an active, inflammatory state (Vivash and O'Brien, 2016). Neurotransmitter levels such as glutamate and GAB could be measured using magnetic resonance spectroscopy (MRS) to provide further evidence of disruption to signalling between neurons and the immune cells (Bertholdo, Watcharakorn and Castillo, 2013; Rae, 2014).

By combining these methods, it could be confirmed if finasteride causes measurable changes in how the brain and immune cells regulate calcium signalling via lipid rafts.

Rebuilding the cells communication network:

If calcium signalling in the cell membrane is part of the problem, repairing the membrane may be the way forward.

Nanoparticles made from natural lipids such as cholesterol are being researched. These biocompatible spheres are often called lipid nanocarriers and they can fuse directly with damaged cell membranes. This would help restore the structure and fluidity and allow calcium channels to resume normal communication between cells(García-Pinel et al., 2019; Levental, Grzybek and Simons, 2010).

Resolvins may also be part of the solution. Resolvins are produced by the body from omega-3 fatty acids and they act as a stop signal for inflammation (Serhan and Levy, 2018). This could help stop the overactivation of brain immune cells linked to PFS symptoms such as anxiety, fatigue and brain fog.

Used together these strategies could help resolve the calcium signalling issue and restore balance.

The Bigger Picture-Why this research matters:

While Post-Finasteride Syndrome remains controversial the impact on patients is real. Understanding why symptoms persist long after the drug has been stopped could give patients hope for treatment and recovery.

The lipid raft calcium signalling hypothesis changes the focus from hormones to look at cell communication and how small imbalances can have huge impacts throughout the body.

References:

Berridge, M. J., Bootman, M. D. and Roderick, H. L. (2003) 'Calcium signalling: dynamics, homeostasis and remodelling', Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 4(7), pp. 517-29.

Bertholdo, D., Watcharakorn, A. and Castillo, M. (2013) 'Brain proton magnetic resonance spectroscopy: introduction and overview', Neuroimaging Clin N Am, 23(3), pp. 359-80.

Brown, D. A. and London, E. (1998) 'Functions of lipid rafts in biological membranes', Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol, 14, pp. 111-36.

Catterall, W. A. (2011) 'Voltage-gated calcium channels', Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol, 3(8), pp. a003947.

Clapham, D. E. (2007) 'Calcium signaling', Cell, 131(6), pp. 1047-58.

Clark, R. V., Hermann, D. J., Cunningham, G. R., Wilson, T. H., Morrill, B. B. and Hobbs, S. (2004) 'Marked suppression of dihydrotestosterone in men with benign prostatic hyperplasia by dutasteride, a dual 5alpha-reductase inhibitor', J Clin Endocrinol Metab, 89(5), pp. 2179-84.

Drake, L., Hordinsky, M., Fiedler, V., Swinehart, J., Unger, W. P., Cotterill, P. C., Thiboutot, D. M., Lowe, N., Jacobson, C., Whiting, D., Stieglitz, S., Kraus, S. J., Griffin, E. I., Weiss, D., Carrington, P., Gencheff, C., Cole, G. W., Pariser, D. M., Epstein, E. S., Tanaka, W., Dallob, A., Vandormael, K., Geissler, L. and Waldstreicher, J. (1999) 'The effects of finasteride on scalp skin and serum androgen levels in men with androgenetic alopecia', J Am Acad Dermatol, 41(4), pp. 550-4.

Duchen, M. R. (2000) 'Mitochondria and calcium: from cell signalling to cell death', J Physiol, 529 Pt 1(Pt 1), pp. 57-68.

Eyo, U. B. and Wu, L. J. (2013) 'Bidirectional microglia-neuron communication in the healthy brain', Neural Plast, 2013, pp. 456857.

Foster, L. J., De Hoog, C. L. and Mann, M. (2003) 'Unbiased quantitative proteomics of lipid rafts reveals high specificity for signaling factors', Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 100(10), pp. 5813-8.

Ganzer, C. A., Jacobs, A. R. and Iqbal, F. (2015) 'Persistent sexual, emotional, and cognitive impairment post-finasteride: a survey of men reporting symptoms', Am J Mens Health, 9(3), pp. 222-8.

García-Pinel, B., Porras-Alcalá, C., Ortega-Rodríguez, A., Sarabia, F., Prados, J., Melguizo, C. and López-Romero, J. M. (2019) 'Lipid-Based Nanoparticles: Application and Recent Advances in Cancer Treatment', Nanomaterials (Basel), 9(4).

Giorgi, C., Agnoletto, C., Bononi, A., Bonora, M., De Marchi, E., Marchi, S., Missiroli, S., Patergnani, S., Poletti, F., Rimessi, A., Suski, J. M., Wieckowski, M. R. and Pinton, P. (2012) 'Mitochondrial calcium homeostasis as potential target for mitochondrial medicine', Mitochondrion, 12(1), pp. 77-85.

Irwig, M. S. (2012) 'Persistent sexual side effects of finasteride: could they be permanent?', J Sex Med, 9(11), pp. 2927-32.

Kettenmann, H., Hanisch, U. K., Noda, M. and Verkhratsky, A. (2011) 'Physiology of microglia', Physiol Rev, 91(2), pp. 461-553.

Kiguradze, T., Temps, W. H., Yarnold, P. R., Cashy, J., Brannigan, R. E., Nardone, B., Micali, G., West, D. P. and Belknap, S. M. (2017) 'Persistent erectile dysfunction in men exposed to the 5α-reductase inhibitors, finasteride, or dutasteride', PeerJ, 5, pp. e3020.

Ledoux, J., Werner, M. E., Brayden, J. E. and Nelson, M. T. (2006) 'Calcium-activated potassium channels and the regulation of vascular tone', Physiology (Bethesda), 21, pp. 69-78.

Levental, I., Grzybek, M. and Simons, K. (2010) 'Greasing their way: lipid modifications determine protein association with membrane rafts', Biochemistry, 49(30), pp. 6305-16.

Melcangi, R. C. and Panzica, G. C. (2006) 'Neuroactive steroids: old players in a new game', Neuroscience, 138(3), pp. 733-9.

Nelson, M. T. and Quayle, J. M. (1995) 'Physiological roles and properties of potassium channels in arterial smooth muscle', Am J Physiol, 268(4 Pt 1), pp. C799-822.

Norden, D. M. and Godbout, J. P. (2013) 'Review: microglia of the aged brain: primed to be activated and resistant to regulation', Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol, 39(1), pp. 19-34.

Rae, C. D. (2014) 'A guide to the metabolic pathways and function of metabolites observed in human brain 1H magnetic resonance spectra', Neurochem Res, 39(1), pp. 1-36.

Rizzuto, R., De Stefani, D., Raffaello, A. and Mammucari, C. (2012) 'Mitochondria as sensors and regulators of calcium signalling', Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 13(9), pp. 566-78.

Russell, D. W. and Wilson, J. D. (1994) 'Steroid 5 alpha-reductase: two genes/two enzymes', Annu Rev Biochem, 63, pp. 25-61.

Serhan, C. N. and Levy, B. D. (2018) 'Resolvins in inflammation: emergence of the pro-resolving superfamily of mediators', J Clin Invest, 128(7), pp. 2657-2669.

Simons, K. and Toomre, D. (2000) 'Lipid rafts and signal transduction', Nat Rev Mol Cell Biol, 1(1), pp. 31-9.

Takahashi, K., Tanabe, K., Ohnuki, M., Narita, M., Ichisaka, T., Tomoda, K. and Yamanaka, S. (2007) 'Induction of pluripotent stem cells from adult human fibroblasts by defined factors', Cell, 131(5), pp. 861-72.

Vivash, L. and O'Brien, T. J. (2016) 'Imaging Microglial Activation with TSPO PET: Lighting Up Neurologic Diseases?', J Nucl Med, 57(2), pp. 165-8.

Zhang, L., Hu, K., Shao, T., Hou, L., Zhang, S., Ye, W., Josephson, L., Meyer, J. H., Zhang, M. R., Vasdev, N., Wang, J., Xu, H., Wang, L. and Liang, S. H. (2021) 'Recent developments on PET radiotracers for TSPO and their applications in neuroimaging', Acta Pharm Sin B, 11(2), pp. 373-393.

Add comment

Comments

Hi, the thought that it is not just about hormones but also how cells communicate through calcium signalling is interesting. But this makes me realise that Finasteride is not the only drug that interferes with sterol metabolism. Why is it that we do not see these persistent neurological changes in Statins, a class of medication that also interfere with sterol metabolism. Maybe it could have something to do with Finasteride tissue specificity?

That's a really good point. I definitely agree that tissue specificity is probably one of the main factors. I also think that what stage in the sterol pathway they act on plays a role, as they work on different steps in cholesterol synthesis. Finasteride is small and lipophilic so probably crosses the blood brain barrier relatively easily which could also be part of the reason we see these changes with Finasteride but not with Statins.

This is very interesting to read about the cell signalling and the impact it has on the body long after the drug has been taken. You have explained it really well. It is fascinating that the recovery speed depends on the speed at which the signalling networks recover. I'm assuming the signalling recovery is different person to person, depending on factors like age, lifestyle and genetics.

You talk about the fact that calcium and potassium channels work hand in hand. Do you think that the calcium hypothesis could be applied to potassium channels also?