The Science of Hair Loss: What is Androgenetic Alopecia (AGA)?

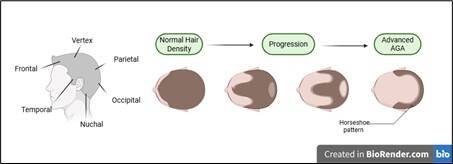

AGA, also known as pattern hair loss, is the most common cause of hair thinning, affecting 80% of men and 50% of women by age 70 (Gupta et al. 2025). At the heart of AGA is a hormone known as dihydrotestosterone (DHT) (Ho et al. 2024). In those genetically predisposed to AGA, DHT binds to androgen receptors (AR), kickstarting the process of follicular miniaturisation. In men, AGA-related hair thinning forms a ‘horseshoe pattern’, as shown in Figure 1 (Lolli et al. 2017).

Figure 1. Illustration of the horseshoe pattern of male hair loss, showing frontal and vertex thinning while the occipital area remains intact. Created in BioRender.com, 2025

This process is driven by 5α-reductase (5α-R), an enzyme that converts testosterone into DHT within cells (Azzouni et al. 2012). Blocking that enzyme, then, seems like a logical solution, and that’s precisely what the drug Finasteride was designed to do.

Understanding Finasteride and How It Changed Hair Loss Therapy

Approved in 1997 for AGA, Finasteride soon gained popularity as one of only two drugs on the market to treat hair thinning (Devjani et al. 2023). Finasteride acts as an inhibitor of type II and III 5α-reductase enzymes, the enzymes responsible for the conversion of testosterone (T) to dihydrotestosterone (DHT), cutting DHT serum levels by approximately 65–70% (Nemane et al. 2019). With less DHT around, hair follicles are spared from miniaturization and growth resumes.

Figure 2. Mechanism of Action of Finasteride and Its Effects on AGA. Created using Canva.com (2025)

When the Cure Becomes the Problem: Post-Finasteride Syndrome

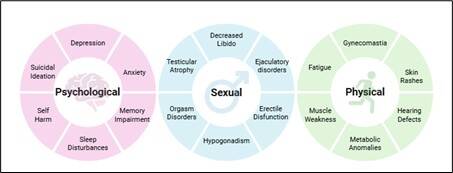

Despite Finasteride’s success in the treatment of hair loss, in recent years, a growing body of clinical reports and patient testimonies has highlighted a concerning pattern: a subset of men experiencing persistent sexual, physical, and psychological symptoms that continue long after discontinuation of the medication. The condition? Post-Finasteride Syndrome (PFS) (Diviccaro et al. 2020). A summarisation of these symptoms is detailed in Figure 3 (Traish, 2020).

Figure 3. A breakdown of the Psychological, Sexual, and Physical Symptoms associated with Post Finasteride Syndrome. Created in BioRender.com (2025)

Despite controversy surrounding the legitimacy of post-finasteride syndrome, the reduced quality of life experienced by those experiencing the persistent symptoms after Finasteride usage warrants further research (Chiriacò et al. 2016).

So what could be causing these lingering symptoms?

The Missing Link: Neurosteroids and Their Role in the Brain

Finasteride’s action isn’t limited to the scalp. The same 5α-reductase enzyme that it blocks in hair follicles is also active in the brain, where it helps produce neurosteroids such as allopregnanolone. Allopregnanolone is a key regulator of GABAA receptors, which play a role in mood disorders (Traish, 2020).

By blocking 5α-reductase, Finasteride also decreases allopregnanolone levels. Studies indicate that low levels of this neurosteroid are associated with depression, anxiety, and post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) (Eser et al. 2006). It offers a potential biological explanation for the psychological symptoms observed in some PFS patients.

Figure 4. Impact of Finasteride treatment on the production of allopregnanolone. Created using Canva.com (2025).

Novel Therapeutics: Restoring Balance Through Neurosteroids

One of the most promising directions in treating the neurological effects of Post-Finasteride Syndrome (PFS) lies not in reversing scalp hormone loss, but in rebalancing the brain.

A possible solution is to restimulate GABAA receptors with a synthetically derived form of allopregnanolone.

A leading candidate is Brexanolone, a synthetic analogue of allopregnanolone, the brain’s natural calming neurosteroid (Cornett et al. 2021). Approved by the FDA in 2019 for postpartum depression, Brexanolone works by enhancing GABAA receptor activity, the same system responsible for relaxation and mood regulation (Cornett et al. 2021).

Its rapid onset, often producing relief within days, has made it an exciting breakthrough (Kanes et al. 2017). But could this exact mechanism offer hope to men with persistent neurological and psychological symptoms after Finasteride use?

Synthetic Allopregnanolone Treatment: Why Brexanolone is setting the standard?

Finasteride’s inhibition of the enzyme 5α-reductase not only lowers dihydrotestosterone (DHT), it also disrupts the synthesis of other neurosteroids, including allopregnanolone (Eser et al. 2006). Low levels of this compound have been linked to anxiety, depression, and cognitive fog (Eser et al. 2006; Traish, 2020).

However, using natural allopregnanolone directly as a drug isn’t practical: it’s poorly soluble in water, breaks down quickly, and can cause sedation at high doses. That’s why researchers created synthetic analogues like Brexanolone, molecules that imitate the brain’s natural neurosteroids but are more soluble, stable, and controllable. (Belelli et al. 2022). A treatment like this, in conjunction with Finasteride, could restore this lost neurochemical balance without reigniting DHT-related hair loss.

To achieve this, analytical techniques such as mass spectrometry, nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR), and high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) are used to confirm the structure, purity, and function of the compounds (Rustichelli et al. 2013).

Formulation chemistry can also be used to overcome solubility issues, improve bioavailability, and ensure ease of administration and safety during intravenous infusion. Allopregnanolone can be dissolved in a carrier molecule, such as sulfobutylether-β-cyclodextrin (SBECD), to reap these benefits. This is how Brexanolone is formulated for use (Kanes et al. 2017; Sarabia-Vallejo et al. 2023).

These innovations transformed a molecule that proved challenging to work with into a deliverable, measurable, and effective medicine.

Restoring Balance: A Neurosteroid Approach to Post-Finasteride Syndrome

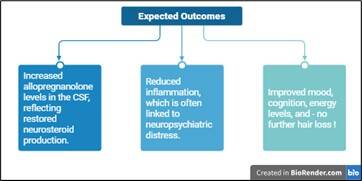

To test whether this therapy could help men with PFS, a double-blind, placebo-controlled trial could be designed, enrolling 80 men aged 18–55 who continue to experience symptoms such as depression, anxiety, and low motivation after discontinuing Finasteride.

Participants would receive a 60-hour IV infusion of an allopregnanolone analogue, modified for stability and solubility with sulfobutylether-β-cyclodextrin (SBECD), or placebo, in a hospital setting, where vital signs and mood changes could be closely monitored (Cornett et al. 2021).

Before and after treatment, researchers would collect blood and cerebrospinal fluid (CSF) samples to measure allopregnanolone levels and inflammatory markers using liquid chromatography–mass spectrometry (LC–MS/MS) (Rustichelli et al. 2013).

They would also assess depressive symptoms using the Montgomery–Åsberg Depression Rating Scale (MADRS) (Montgomery and Åsberg 1979).

Figure 5. Proposed results after treatment with Allopregnanolone. Created in Biorender.com (2025)

Beyond the Scalp: Why It Matters

If future neurosteroid-based treatments can reverse PFS symptoms, it would represent a significant leap in neuroendocrinology, offering proof that hormonal balance and mental health are deeply interconnected.

For patients, it could mean not just symptom relief, but the restoration of a sense of normalcy and confidence lost after treatment.

Perhaps the most remarkable aspect is that this approach targets brain chemistry rather than DHT levels.

That means patients can treat neurological side effects without losing the hair-growth benefits that Finasteride provides —a genuine win-win for both body and mind.

The Bigger Picture

Androgenetic alopecia might begin on the scalp, but its story runs far deeper, into the brain, hormones, and mental health.

Finasteride remains a cornerstone in combating hair loss, yet as science uncovers its broader effects, researchers are recognizing that proper recovery means treating the whole person.

By blending modern analytical chemistry, neurobiology, and clinical innovation, neurosteroid-based treatments, such as allopregnanolone analogues like Brexanolone, could redefine how we think about the intersection between hormones and the mind.

Every discovery, even those born from side effects, brings medicine one step closer to understanding and restoring balance.

Bibliography

Azhar, Y. and Din, A.U. (2025) ‘Brexanolone’, in StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541054/ [accessed 29 Oct 2025].

Azzouni, F., Godoy, A., Li, Y., and Mohler, J. (2012) ‘The 5 Alpha-Reductase Isozyme Family: A Review of Basic Biology and Their Role in Human Diseases’, Advances in Urology, 2012, 1–18, available: https://doi.org/10.1155/2012/530121.

Baas, W.R., Butcher, M.J., Lwin, A., Holland, B., Herberts, M., Clemons, J., Delfino, K., Althof, S., Kohler, T.S., and McVary, K.T. (2018) ‘A Review of the FAERS Data on 5-Alpha Reductase Inhibitors: Implications for Postfinasteride Syndrome’, Urology, 120, 143–149, available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.urology.2018.06.022.

Belelli, D., Peters, J.A., Phillips, G.D., and Lambert, J.J. (2022) ‘The immediate and maintained effects of neurosteroids on GABAA receptors’, Current Opinion in Endocrine and Metabolic Research, 24, 100333, available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coemr.2022.100333.

Chiriacò, G., Cauci, S., Mazzon, G., and Trombetta, C. (2016) ‘An observational retrospective evaluation of 79 young men with long‐term adverse effects after use of finasteride against androgenetic alopecia’, Andrology, 4(2), 245–250, available: https://doi.org/10.1111/andr.12147.

Cornett, E.M., Rando, L., Labbé, A.M., Perkins, W., Kaye, A.M., Kaye, A.D., Viswanath, O., and Urits, I. (2021) ‘Brexanolone to Treat Postpartum Depression in Adult Women’, Psychopharmacology Bulletin, 51(2), 115–130, available: https://doi.org/10.64719/pb.4397.

Devjani, S., Ezemma, O., Kelley, K.J., Stratton, E., and Senna, M. (2023) ‘Androgenetic Alopecia: Therapy Update’, Drugs, 83(8), 701–715, available: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40265-023-01880-x.

Diviccaro, S., Melcangi, R.C., and Giatti, S. (2020) ‘Post-finasteride syndrome: An emerging clinical problem’, Neurobiology of Stress, 12, 100209, available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ynstr.2019.100209.

Diviccaro, S., Oleari, R., Amoruso, F., Fontana, F., Cioffi, L., Chrostek, G., Abenante, V., Troisi, J., Cariboni, A., Giatti, S., and Melcangi, R.C. (2025) ‘Exploration of the Possible Relationships Between Gut and Hypothalamic Inflammation and Allopregnanolone: Preclinical Findings in a Post-Finasteride Rat Model’, Biomolecules, 15(7), 1044, available: https://doi.org/10.3390/biom15071044.

Eser, D., Romeo, E., Baghai, T.C., Di Michele, F., Schüle, C., Pasini, A., Zwanzger, P., Padberg, F., and Rupprecht, R. (2006) ‘Neuroactive steroids as modulators of depression and anxiety’, Neuroscience, 138(3), 1041–1048, available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neuroscience.2005.07.007.

Gupta, A.K., Wang, T., and Economopoulos, V. (2025) ‘Epidemiological landscape of androgenetic alopecia in the US: An All of Us cross-sectional study’, PLOS ONE, 20(2), e0319040, available: https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0319040.

Ho, C.H., Sood, T., and Zito, P.M. (2024) ‘Androgenetic Alopecia’, in StatPearls [Internet], StatPearls Publishing, available: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/sites/books/NBK430924/ [accessed 29 Oct 2025].

Kanes, S.J., Colquhoun, H., Doherty, J., Raines, S., Hoffmann, E., Rubinow, D.R., and Meltzer-Brody, S. (2017) ‘Open-label, proof-of-concept study of brexanolone in the treatment of severe postpartum depression’, Human Psychopharmacology: Clinical and Experimental, 32(2), e2576, available: https://doi.org/10.1002/hup.2576.

King, S.R. (2013) ‘Neurosteroids and the Nervous System’, in King, S.R., ed., Neurosteroids and the Nervous System, New York, NY: Springer, 1–122, available: https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4614-5559-2_1.

Lolli, F., Pallotti, F., Rossi, A., Fortuna, M.C., Caro, G., Lenzi, A., Sansone, A., and Lombardo, F. (2017) ‘Androgenetic alopecia: a review’, Endocrine, 57(1), 9–17, available: https://doi.org/10.1007/s12020-017-1280-y.

Martin, K.A., Anderson, R.R., Chang, R.J., Ehrmann, D.A., Lobo, R.A., Murad, M.H., Pugeat, M.M., and Rosenfield, R.L. (2018) ‘Evaluation and Treatment of Hirsutism in Premenopausal Women: An Endocrine Society* Clinical Practice Guideline’, The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology & Metabolism, 103(4), 1233–1257, available: https://doi.org/10.1210/jc.2018-00241.

McClellan, K.J. and Markham, A. (1999) ‘Finasteride: A Review of its Use in Male Pattern Hair Loss’, Drugs, 57(1), 111–126, available: https://doi.org/10.2165/00003495-199957010-00014.

Montgomery, S.A. and Åsberg, M. (1979) ‘A New Depression Scale Designed to be Sensitive to Change’, British Journal of Psychiatry, 134(4), 382–389, available: https://doi.org/10.1192/bjp.134.4.382.

Nemane, S.T., Bhusnure, O.G., Gholve, S.B., Mitakari, P.R., and Karwa, P.N. (2019) ‘A Review on Finasteride: A 5-Alpha Reductase Inhibitor, its Mechanism, Facts and Benefits’, Journal of Drug Delivery and Therapeutics, 9(3-s), 1132–1136, available: https://doi.org/10.22270/jddt.v9i3-s.3013.

Rustichelli, C., Pinetti, D., Lucchi, C., Ravazzini, F., and Puia, G. (2013) ‘Simultaneous determination of pregnenolone sulphate, dehydroepiandrosterone and allopregnanolone in rat brain areas by liquid chromatography–electrospray tandem mass spectrometry’, Journal of Chromatography B, 930, 62–69, available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jchromb.2013.04.035.

Sarabia-Vallejo, Á., Caja, M.D.M., Olives, A.I., Martín, M.A., and Menéndez, J.C. (2023) ‘Cyclodextrin Inclusion Complexes for Improved Drug Bioavailability and Activity: Synthetic and Analytical Aspects’, Pharmaceutics, 15(9), 2345, available: https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics15092345.

Traish, A.M. (2020) ‘Post-finasteride syndrome: a surmountable challenge for clinicians’, Fertility and Sterility, 113(1), 21–50, available: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.11.030.

Trüeb, R.M., Régnier, A., Dutra Rezende, H., and Gavazzoni Dias, M.F.R. (2019) ‘Post-Finasteride Syndrome: An Induced Delusional Disorder with the Potential of a Mass Psychogenic Illness?’, Skin Appendage Disorders, 5(5), 320–326, available: https://doi.org/10.1159/000497362.

Zito, P.M., Bistas, K.G., Patel, P., and Syed, K. (2025) ‘Finasteride’, in StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK513329/ [accessed 29 Oct 2025].

Add comment

Comments

Your blog is a brilliant presentation of the neurosteroid hypothesis of the Post-Finasteride Syndrome (PFS), which indicates the central allopregnanolone deficiency as the potential cause of the neuropsychiatric symptoms, and the related sexual and physical side effects are potentially long-term and extend to peripheral androgen receptor (AR) dysfunction. It is not clear that neurosteroid-based interventions, such as Brexanolone, can be selectively used to restore neurosteroid levels in the brain without affecting peripheral AR activity. The distinction should be studied in future to allow such therapies to be used effectively to target the central symptoms without causing undesirable hormonal events.

Thanks so much for reading my blog, Rimsha. You make a great point. At the moment, we don’t know if neurosteroid treatments like brexanolone can boost allopregnanolone in the brain without also affecting androgen signalling in the rest of the body.

Since PFS might involve both central neurosteroid changes and peripheral AR dysfunction, targeting only the brain may not fix every symptom. Future research really needs to separate these two areas so treatments can focus on the neurological side without causing unwanted hormonal effects.

It’s an important distinction and one that definitely needs more study!

I thought your blog did a fantastic job of explaining how finasteride causes these depressive tendencies and how this manifests biologically through blocking the enzyme 5α-reductase . The benefits of finasteride in treating androgenetic alopecia are clear but its use must be very closely monitored to prevent the occurrence of these troubling side effects.

The idea of using a synthetic analogue like brexanolone is a great way of mitigating the negative effects of finasteride and keeping its benefits. I was intrigued by this and found there are many potential uses of analogues in treating hormonal imbalances. While commonly used for treating post-partum depression, I found that it is being investigated for a range of uses, even in cases such as mitigating against alcohol withdrawal, whereby misuse of alcohol has decreased allopregnanolone levels (Gatta et al., 2022).

What are the potential dangers of using a neurosteroid analogue? Could we see any unexpected results? I found that work by (FDA., 2018) has found that brexanolone has the potential for abuse in humans. Do you think this could prove a cause for concern in the continued development of neurosteroid analogues?

References:

• Gatta, E., Camussi, D., Auta, J., Guidotti, A. and Pandey, S.C. (2022). Neurosteroids (allopregnanolone) and alcohol use disorder: From mechanisms to potential pharmacotherapy. Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 240, p.108299. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pharmthera.2022.108299.

• Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research: NDA 211371 Multi-disciplinary review and evaluation. 2018 (https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2019/211371Orig1s000MultidisciplineR.pdf)

Hi Jack, thanks so much for taking the time to read my blog! I really appreciate your thoughtful engagement, and you brought up a point I hadn’t considered in much depth before, which is the potential for these drugs to be misused.

I also appreciate that you looked into brexanolone further. The fact that neurosteroid analogues are now being explored for such a wide range of conditions, including alcohol withdrawal, makes this a really exciting area of research!

That said, they do come with some risks. Because they boost GABA activity, they can cause strong sedation, interact with alcohol or other depressants, and occasionally lead to short term mood changes (Maguire and Mennerick 2024). Since these drugs can also produce a calming effect similar to other positive allosteric modulators of the GABA receptor, such as benzodiazepines, the potential for misuse is probably the biggest concern (Maguire and Mennerick 2024).

This is exactly why the FDA flagged brexanolone for potential abuse and why the treatment is only given through a supervised 60 hour infusion (U.S. Food and Drug Administration, 2019; Azhar and Din 2025). That level of monitoring keeps people safe and makes it very difficult for the drug to be misused.

I don’t think this will stop new neurosteroid treatments from being developed, but it definitely shapes how they are designed. Researchers now need to focus on versions that are safer, harder to misuse, and more tightly controlled in how they affect the brain.

So while it’s something worth keeping in mind, I don’t think it’s a dealbreaker. With proper monitoring and smart drug design, neurosteroid analogues could still be very helpful for people with PFS and other conditions.

References

Azhar, Y. and Din, A.U. (2025) ‘Brexanolone’, in StatPearls, Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing, available: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541054/ [accessed 28 Nov 2025].

Maguire, J.L. and Mennerick, S. (2024) ‘Neurosteroids: mechanistic considerations and clinical prospects’, Neuropsychopharmacology, 49(1), 73–82, available: https://doi.org/10.1038/s41386-023-01626-z. [accessed 28 Nov 2025].

U.S. Food and Drug Administration (2019) Other reviews: NDA 211371 – Zulresso (brexanolone), original submission 1 (s000), available: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/nda/2019/211371Orig1s000OtherR.pdf [accessed 28 Nov 2025].