Mothers are notorious for selflessness. It’s built into being a mother, making sacrifices to see your little-one thrive. As a mother with RRMS, choosing between a drug that decreases relapses, and the intimacy and benefits that breastfeeding provides, is an impossible feat. Many DMTs (Disease-modifying therapies) are not compatible with breastfeeding, so many mothers will forego their treatment, to breastfeed (Gklinos et al, 2023). However, the benefits and protection that breastfeeding can provide for RRMS sufferers often doesn’t compare to the relief a DMT can provide. What if you didn’t have to choose? Why can’t a mother have it all? Let’s figure it out!

What is MS?

Multiple Sclerosis is an autoimmune disease that attacks the central nervous system. B and T cells attack the myelin coating on the axon of neurons, leading to degeneration (Marcus, 2022). Oligodendrocytes, which are responsible for creating the myelin sheaths, are also damaged by immune cells, making regeneration harder. This combination of lack of regeneration and consistent degeneration can lead to many symptoms. The most common of which include fatigue, emotional changes, difficulty walking, and vision problems. Chronic pain is one of the most disabling symptoms of MS, along with anxiety and depression generated from brain lesions, drastically impacting quality of life.

MS can be diagnosed by seeing these lesions along the CNS through MRI. A lumbar puncture is also often performed which involves a sample of cerebrospinal fluid being taken (Zajicek, 2001). A specialist will then look at this fluid to identify any abnormalities that could be associated with MS.

Relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS) is the most common form of MS and is characterised by sudden symptoms (relapse) followed by a period of recovery (remission) (Marcus, 2022). Eventually, the oligodendrocytes which contribute to remission can be degraded, or the severity of the relapse can increase, meaning that the degree of disability worsens with age. Another classification is primary-progressive MS (PPMS) which is characterized by the consistent worsening of symptoms over time. A person with PPMS doesn’t experience relapses or remission.

^ Figure 1: Degeneration of Neuron due to Multiple Sclerosis. 1. Demonstrates a healthy neuron with myelin (yellow) protecting the axon. Oligodendrocytes (dark green) can be seen maintaining and creating new myelin along the axon. 2. B and T Cells (light blue and green) can be seen degenerating the myelin, exposing the axon. 3. Degenerated neuron incapable of communication (Created in Biorender).

What Factors Contribute to MS?

Studies indicate that several things can increase your likelihood of developing MS. Environmentally these include low vitamin-D levels, early life obesity, and smoking (Rodrigues et al, 2023). Interestingly, the ratio of women to men with the disease is now 3:1, however men tend to have a more rapidly-progressing form of the disease. This ratio of more female patients than male has not always been the case, however there are not less men suffering from this disease, just an increase in women suffering (Wang et al, 2023)! As of this February, it was reported that the global number of MS patients has risen to 1.89 million people! Ireland reported the fourth highest number of cases worldwide with 163 cases per 100,000 people (Khan et al, 2025).

Breastfeeding and RRMS

Breastfeeding is associated with less relapses in RRMS (Portaccio et al, 2019). This can be down to many reasons, from hormone changes to immune system changes. These mechanisms are very complex and still being researched currently. Disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) can treat RRMS very effectively by altering how our immune system functions to prevent it attacking the CNS (central nervous system). However, a high number of them require a stop in breastfeeding due to the medication contaminating the breastmilk. For many women, stopping treatment to breastfeed is not an option. As of now, we have no cure, but we can, however, investigate ways we can try and lessen your symptoms, while ensuring the safety of your little one. Let’s discuss current treatments, and then theorise alternative solutions that have potential to be the best of both worlds

Current Treatments

A current treatment for RRMS in Teriflunomide (Aubagio). This drug works by inhibiting dihydroorate dehydrogenase (DHODH), which is found in the mitochondria and involved in the mechanism of proliferating T cells and B cells, leading to increased inflammation and neuronal degradation (Bar-Or, 2014). Therefore, Teriflunomide helps to reduce inflammation in the CNS, leading to a reduction in relapses. However, Aubagio is not recommended when breastfeeding due to its long half-life, and transfer to breast milk, meaning it’s not safe for infant consumption.

Another treatment is Alemtuzumab. This is a IgG1 antibody which binds to a protein called CD52. CD52 is small and is believed to be a marker of mature immune cells. The binding of this drug to CD52 aims to reduce pathogenic immune cell activity, and hence the degradation of the myelin on a neuron (Ruck, et al, 2015). This drug is not suitable during breastfeeding because any medication that suppresses your immune system will affect your baby’s immune system!

Potential Future Treatments? Let’s explore

Let’s keep looking at DMTs. But instead of inhibiting DHODH like Aubagio, we need to find another protein or molecule involved in the production of B and T cells that we can inhibit, without risking baby’s health!

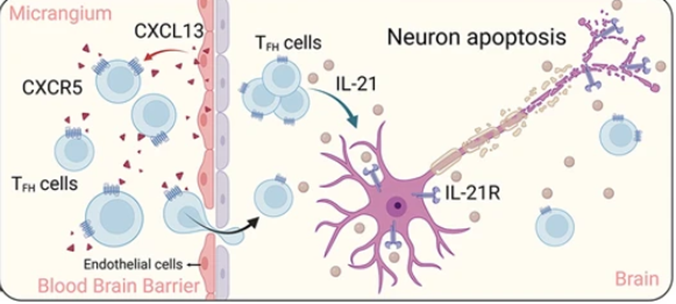

I propose we target the CXCL13-CXCR5 pathway to reduce follicle driven hostile immune activity. This topic has been explored for other diseases such as ALS, but not yet MS. CXCR5 is a GPCR (G protein coupled receptor). CXCL13 is its corresponding ligand (Zheng et al, 2024). CXCL13 guides B-cells to lymphoid follicles and inflamed CNS tissue (Burger et al, 2014). However, a slight overexpression in CXCL13 can lead to a hostile immune response, which, downstream, can lead to the lesions that characterise MS, bolstering relapses.

^ Figure 2: Example of one mechanism mediated by CXCR5-CXCL13 leading to neuronal death, (Zheng et al, 2024)

A drug that could inhibit this receptor would lead to less interactions that promote B-cell activation, therefore less inflammation in the CNS. This coupled with the already neuroprotective benefits of breastfeeding could potentially reduce the number or severity of relapses a breastfeeding mother would experience. An antibody would be the best choice for this as large molecules are a safe option when breastfeeding as they are not well absorbed by babies. However, to ensure its safety while breastfeeding, several extra trials would be needed when investigating this as a drug option.

How would we test this as an option?

-

Finding an Inhibitor

We first need to find something that block CXCR5, stopping CXCL13 from binding to it. To do this we can find an existing inhibitor or construct one.

This would involve a lengthy screening process trialling many different proteins. Or, an inhibitor could be engineered by studying the molecular composition of both CXCR5 and CXCL13.

-

Testing its efficacy

To test our theory, we would start with in-vitro trials. We could test our inhibitors binding affinity using flow cytometry, using CXCR5 negative cells as a control, or, if using an engineered inhibitor, using a known CXCR5 inhibitor as a control.

Flow Cytometry could also be used to see if our inhibitor can beat CXCL13 to block CXCR5 (Gascue et al, 2018). This would be done by comparing fluorescence of the two proteins binding with and without our engineered inhibitor.

We could then use ELISAs to test the downstream effects of our inhibitor. Selectively figure out what is and isn’t activated when we inhibit CXCR5

To test our drug in-vivo, an EAE mouse could be used. These mice develop nerve problems and can suffer relapses in similar fashion to MS (Dedoni et al, 2023). Thorough testing here would involve observing symptoms of the mice, using imaging to monitor an improvement or worsening of lesions, and keeping a consistent count of B and T cells and their location in the body.

-

Testing its safety

Testing its safety would also involve EAE mice. Observing all the points made above regarding efficacy; while giving the mice different dosages of the drug will help us to ascertain the lethal-dosage (LD) limit, and EC50 which will help us determine a safe potency.

To test its safety regarding breastfeeding, these mice are ideal candidates as they breastfeed their pups. Testing the milk from these EAE mice both with our inhibitor and without, along with the blood of the pups, will help us determine if there has been any milk transfer, or if the antibody has altered the immune system of the pups in any way. The B and T cell levels and location within the pups should also be observed, in the same way it was in initial in vivo trials.

Creating and testing the efficacy of such a drug would take arduous amount of time and resources. However, with most patients with MS being women of childbearing age, I believe it is worth the process.

Potential for Further Study

Multiple Sclerosis is an incredibly complex disease. So much work as been done to unravel its complexities yet still so much remains unknown. Valuable research could be done regarding its increasing prevalence in women. Cases of MS in women have increased exponentially in the last decade. What has changed in this time that has driven such a large incidence rate?

There are many other areas of study in the immune system that could yet reveal innovative ways of reducing relapse-rates in MS patients, such as further investigation into how HDAC6 inhibition or SIRT1 inhibition could alter inflammatory effects downstream, and could this be used to alleviate symptoms (LoPresti, 2020)?

Importance

With such high numbers of patients worldwide, there are few people who haven’t been touched by the debilitating effects of MS. Becoming a mother is a scary, exciting, draining, exhilarating experience, and having RRMS shouldn’t take away from that. Investigating DMTs compatible with breastfeeding could allow mothers with RRMS to experience motherhood with only their little one at the forefront of their mind.

References

Gklinos, P., & Dobson, R. (2023). Monoclonal Antibodies in Pregnancy and Breastfeeding in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis: A Review and an Updated Clinical Guide. Pharmaceuticals (Basel, Switzerland), 16(5), 770. https://doi.org/10.3390/ph16050770

Marcus, R. (2022) 'What is multiple sclerosis?,' JAMA, 328(20), p. 2078. https://doi.org/10.1001/jama.2022.14236.

Zajicek, J. (2001) 'Multiple sclerosis. Diagnosis, Medical Management and Rehabilitation,' Journal of Neurology Neurosurgery & Psychiatry, 70(3), pp. 421b–4421. https://doi.org/10.1136/jnnp.70.3.421b.

Khan, G., & Hashim, M. J. (2025). Epidemiology of Multiple Sclerosis: Global, Regional, National and Sub-National-Level Estimates and Future Projections. Journal of epidemiology and global health, 15(1), 21. https://doi.org/10.1007/s44197-025-00353-6

Portaccio E, Amato MP. Breastfeeding and post-partum relapses in multiple sclerosis patients. Multiple Sclerosis Journal. 2019;25(9):1211-1216. doi:10.1177/1352458519830588

Patrícia Rodrigues, Brenda da Silva, Gabriela Trevisan, A systematic review and meta-analysis of neuropathic pain in multiple sclerosis: Prevalence, clinical types, sex dimorphism, and increased depression and anxiety symptoms, Neuroscience & Biobehavioral Reviews, Volume 154, 2023, 105401, ISSN 0149-7634, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.neubiorev.2023.105401.

Yinxiang Wang, Jue Wang, Juan Feng, Multiple sclerosis and pregnancy: Pathogenesis, influencing factors, and treatment options, Autoimmunity Reviews, Volume 22, Issue 11, 2023, 103449, ISSN 1568-9972, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.autrev.2023.103449.

Bar-Or A. (2014). Teriflunomide (Aubagio®) for the treatment of multiple sclerosis. Experimental neurology, 262 Pt A, 57–65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.expneurol.2014.06.005

Ruck, T., Bittner, S., Wiendl, H., & Meuth, S. G. (2015). Alemtuzumab in Multiple Sclerosis: Mechanism of Action and Beyond. International journal of molecular sciences, 16(7), 16414–16439. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijms160716414

Zheng, K., Chen, M., Xu, X. et al. Chemokine CXCL13–CXCR5 signaling in neuroinflammation and pathogenesis of chronic pain and neurological diseases. Cell Mol Biol Lett 29, 134 (2024). https://doi.org/10.1186/s11658-024-00653-y

Jan A. Burger, John G. Gribben, The microenvironment in chronic lymphocytic leukemia (CLL) and other B cell malignancies: Insight into disease biology and new targeted therapies, Seminars in Cancer Biology, Volume 24, 2014, Pages 71-81, ISSN 1044-579X, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.08.011.

Gascue, A., Merino, J., & Paiva, B. (2018). Flow Cytometry. Hematology/oncology clinics of North America, 32(5), 765–775. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hoc.2018.05.004

Dedoni, S., Scherma, M., Camoglio, C., Siddi, C., Dazzi, L., Puliga, R., Frau, J., Cocco, E., & Fadda, P. (2023). An overall view of the most common experimental models for multiple sclerosis. Neurobiology of disease, 184, 106230. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.nbd.2023.106230

LoPresti P. (2020). HDAC6 in Diseases of Cognition and of Neurons. Cells, 10(1), 12. https://doi.org/10.3390/cells10010012

Add comment

Comments

This was a great read, very complex trying to overcome this challenge which is affecting so many people. A large molecule drug sounds like a great idea to help prevent the breast milk from contamination. I wonder if it was engineered to contain a localisation signal would it be possible to keep the drug away from breast milk production ? I also wonder what challenges would be faced trying to get a large molecule drug passed the blood brain barrier. Great blog!

Thank you Eimear! That's an interesting idea and definitely worth looking into. Perhaps a combination of that and engineering of the Fc region of the antibody could be a step in the right direction?

In terms of crossing the BBB that is definitely a limitation of my proposal, however I think its worth further study, potentially into conjugation with BBB active peptides to enhance or increase uptake