Why do breastfeeding mothers hold the key to Myelin repair?

Multiple sclerosis (MS) is a chronic autoimmune disease of the central nervous system. This disease is primarily caused by an attack of the immune system on the protective barrier of the nerve cells, known as myelin, leading to nerve damage (demyelination) resulting in a host of physical and cognitive difficulties in patients. Patients go through phases of remission and relapse where their symptoms may improve and worsen throughout their lifetime.

Fig. 1 – The axon and myelin sheath

However, a study performed by Confavreux et. al. in 1998 (1) examined 227 pregnant women diagnosed with MS throughout, and 12 months following their pregnancies. Their findings suggested that women who exclusively breast fed their infants experienced a lower relapse rate than women that did not breastfeed (see fig.2)

Fig.2 – Rate of relapse among women with MS in relation to breastfeeding by Confavreux et. al. in 1998 (1)

This has led the scientific community to ask the question: “Could the neuroprotective effect of breastfeeding be used to find a new treatment of MS?”

How does breastfeeding protect mothers from MS?

A study performed by Mouilhate A. and Kalakh in 2023 (2) on rats found that Lactation increased the expression of long-form myelin-associated glycoprotein (L-MAG). This protein plays a crucial role in the formation and maintenance of myelinated axons. Mutation of L-MAG is also associated to neurological disorders – including MS. Pronker et. al. 2016 (3).

So, what is L-MAG?

L-MAG is a protein found in the non-compacted paranodal area of the myelin sheath. Aggarwal et. al. 2011 (4). L-MAG is believed to interact with myelin and is involved in the build-up of the myelin sheath during myelination. A further study led by Nobuya Fujita in 1998 studying the Cytoplasmic Domain of the Large Myelin-Associated Glycoprotein Isoform in mice discovered the presence of cytoplasm within the myelin lamella. This can usually be seen in the initial stages of myelination suggesting that L-MAG plays a crucial role in the early development and maintenance of the myelin sheath. Fujita et.al.1998 (5). It was also noted that the mutant mice displayed a considerable number of oligodendroglia processes encircling one single axonal segment. The results indicate that the presence of the cytoplasmic properties of L-MAG affects the signalling interactions among oligodendrocytes – the cells responsible for myelin formation around axons.

Can E. coli be the answer for L-MAG therapeutics?

To obtain the L-MAG needed for this therapy we propose to produce L-MAG recombinantly in a microbial system. The use of recombinant proteins has many advantages compared to traditionally produced proteins. They are quick, simple and cost effective to produce. Rosano et. al. 2014 (6).

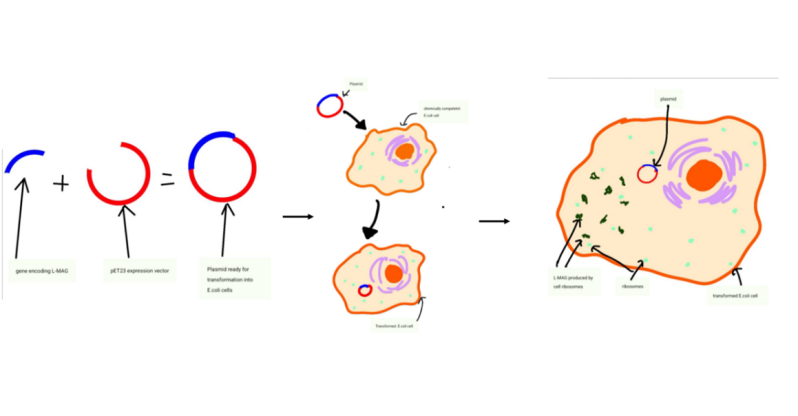

Recombinant protein production is simple in theory. A gene encoding your protein of interest is cloned into a chosen expression vector creating a plasmid. The plasmid is then inserted into chemically competent cells such as E. coli. E. coli has thus gained a reputation as a cell factory and is the most popular expression platform used for recombinant protein production. Rosano, G.L. and Ceccarelli, E.A., 2014 (6).

A chemical transformation could be carried out to insert the L-MAG gene into the chosen E. coli cells. The protein gene would then be expressed within these cells, resulting in the L-MAG protein being produced by the cell ribosomes. The protein could then be extracted from the E. coli cells and purified using methods such as Ion Metal Affinity Chromatography (IMAC), Structural Genomics Consortium, 2008 (7). To produce L-MAG we suggest the use of the Bl21 (DE3) pLysS E. coli strain due to its high suitability for recombinant protein production, and the pET23 expression system due to its ease of use. Rosano, G.L. and Ceccarelli, E.A., 2014 (6).

Fig. 3 – Recombinant Protein Production in E. coli cells

How is the L-MAG delivered to the brain?

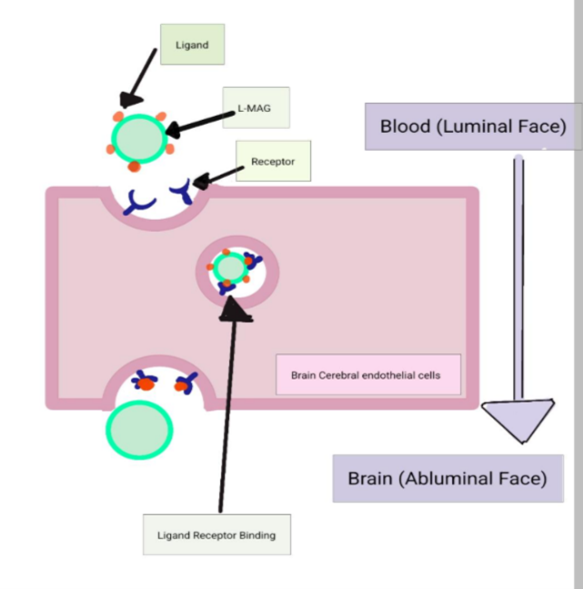

The delivery of therapeutic proteins to the brain can be complex and challenging and there are many factors to consider. L-MAG by itself cannot passively cross the BBB due its size (100 KDA) Lopez, P.H, 2014 (8) and its hydrophilic nature. L-MAG cannot fit through tight junctions and cannot diffuse directly through the cell membrane. Lopez, P.H, 2014 (8). It therefore requires a specific transfer mechanism across the endothelial cells of the BBB. In addition to this free L-MAG may also generate an immune response in the patients which is a known problem of protein-based therapeutics Sauna Z.E. 2020 (9). One way to avoid triggering the immune system is liposome encapsulation Large, DE. et. al. 2021 (10). Receptor-mediated transcytosis (RMT) can then be used as a mode of transport to cross the BBB. Large, DE. et. al. 2021 (10). Other benefits of liposome encapsulation as a delivery mechanism has benefits such as prolonged circulation time in the bloodstream, improved drug stability and can be engineered to target specific sites in the body. Juhairiyah, F. and De Lange, E.C.2021 (11).

The protein is first encapsulated into vesicles using thin film hydration to coat the L-MAG protein molecules creating uniform vesicles which are then functionalised with Transferrin ligands. Jones, AR. and Shusta, E.V., 2007 (12). These transferrin ligands will then bind to transferrin receptors (TfR1) on the luminal side of the endothelial cells of the capillaries making up the blood brain barrier (BBB). The receptor ligand complex is then internalized by the endothelial cells and then released on the abluminal side of the endothelial cells, thus releasing the therapeutic molecule into the brain. This overcomes the issue of transporting L-MAG across the blood brain barrier. Baghirov, H., 2025 (13).

Fig.4 – Transport of encapsulated L-MAG across the blood brain barrier.

What can this novel approach achieve?

Once delivered to the brain we believe that the supplemented L-MAG will enhance and support the remyelination of the myelin sheaths which have been damaged by an autoimmune attack because of multiple sclerosis. By supplementing L-MAG in this way we hope that this novel therapy will recreate the promyelinating effects of lactation in all MS patients. The benefit of this potential therapy is that it can be used in both male and female patients (who are not necessarily breastfeeding) alongside existing therapies for MS. Therefore, this will mimic the reduction of relapse rates as seen from breastfeeding mothers and will hopefully reduce symptoms and improve quality of life for all MS patients.

References

- Confavreux, C., Hutchinson, M., Hours, M.M., Cortinovis-Tourniaire, P., Moreau, T. and Pregnancy in Multiple Sclerosis Group, 1998. Rate of pregnancy-related relapse in multiple sclerosis. New England Journal of Medicine, 339(5), pp.285-291.

- Mouihate, A. and Kalakh, S., 2023. Breastfeeding promotes oligodendrocyte precursor cells division and myelination in the demyelinated corpus callosum. Brain Research, 1821, p.148584.

- Pronker, M.F., Lemstra, S., Snijder, J., Heck, A.J., Thies-Weesie, D.M., Pasterkamp, R.J. and Janssen, B.J., 2016. Structural basis of myelin-associated glycoprotein adhesion and signalling. Nature communications, 7(1), p.13584.

- Aggarwal, S., Yurlova, L., Snaidero, N., Reetz, C., Frey, S., Zimmermann, J., Pähler, G., Janshoff, A., Friedrichs, J., Müller, D.J. and Goebel, C., 2011. A size barrier limits protein diffusion at the cell surface to generate lipid-rich myelin-membrane sheets. Developmental cell, 21(3), pp.445-456.

- Fujita, N., Kemper, A., Dupree, J., Nakayasu, H., Bartsch, U., Schachner, M., Maeda, N., Suzuki, K., Suzuki, K. and Popko, B., 1998. The cytoplasmic domain of the large myelin-associated glycoprotein isoform is needed for proper CNS but not peripheral nervous system myelination. Journal of Neuroscience, 18(6), pp.1970-1978.

- Rosano, G.L. and Ceccarelli, E.A., 2014. Recombinant protein expression in Escherichia coli: advances and challenges. Frontiers in microbiology, 5, p.172.

- Structural Genomics Consortium, 2008. Protein production and purification. Nature methods, 5(2), pp.135-146.

- Lopez, P.H., 2014. Role of myelin-associated glycoprotein (siglec-4a) in the nervous system. In Glycobiology of the Nervous System(pp. 245-262). New York, NY: Springer New York.

- Sauna, Z.E., 2020. Immunogenicity of protein-based therapeutics. US Food and Drug Administration. Retrieved, 6.

- Large, D.E., Abdelmessih, R.G., Fink, E.A. and Auguste, D.T., 2021. Liposome composition in drug delivery design, synthesis, characterization, and clinical application. Advanced drug delivery reviews, 176, p.113851.

- Juhairiyah, F. and De Lange, E.C., 2021. Understanding drug delivery to the brain using liposome-based strategies: studies that provide mechanistic insights are essential. The AAPS Journal, 23(6), p.114.

- Jones, A.R. and Shusta, E.V., 2007. Blood–brain barrier transport of therapeutics via receptor-mediation. Pharmaceutical research, 24(9), pp.1759-1771.

- Baghirov, H., 2025. Beyond the blood–brain barrier: the fate of transcytosed therapeutics. Trends in Pharmacological Sciences.

Add comment

Comments

This is a really cool idea, I love the use of recombinant proteins for this. Do you have any insight as to whether or not this would contaminate the breastmilk in patients who are breastfeeding? Depending on how it affects the milk is it likely to induce an immune response from the child?

Thank you Andrea that is a very good question.

So, liposomes are specifically engineered to deliver drug to their target sites. In our case we chose to specifically induce recombinant L-MAG protein directly to the blood brain barrier to avoid exposing the protein to other tissues, such as the breast tissue. In this way we believe that it is very unlikely that the breast milk would be affected or that an immune response would be triggered. L-MAG naturally forms from lactation and has shown to play a crucial role in repairing the myelin sheath. This is what inspired us to use the protective role of L-MAG for MS patients.

This blog was fascinating to read! The idea of producing L-MAG recombinantly using E. coli is particularly interesting; however, I was curious about the choice of expression system.

Why was E. coli chosen for producing the L-MAG protein instead of using a mammalian expression system, such as CHO cells, which are widely used in the pharmaceutical industry for producing complex therapeutic proteins like antibodies?

Would using E. coli have any limitations in terms of how well the L-MAG protein folds or functions compared to if it were produced in a mammalian cell line, or is the bacterial system mainly preferred because it’s faster and more cost-effective for research purposes?

Thank you Ava! Glad you enjoyed the blog! Recombinant protein production is a really exciting middle ground between Biochemistry and Microbiology - so it was pretty much right up our alley!

You're correct that a mammalian expression system eg. CHO Cells as given above, would have some advantages for the production of L-MAG. CHO cells contain several mechanisms required for post-translational modifications such as glycosylation and phosphorylation, as well as the endoplasmin reticulum which aids in correct protein folding. Microbial systems lack these mechanisms which can result in issues such as inclusion bodies, poor yields and poor quality proteins. However - many of these obstacles can be overcome!

Microbial expression systems have many advantages compared to mammalian systems such as CHO cells. E.coli has an extremely quick doubling time (about 20 minutes) meaning that an entire protein can be ( in theory) transformed, produced in culture and purified within 1 to 2 days . E.coli are also simple and inexpensive to culture, they are easy to scale and don't require complex culture media and bioreactors. However most importantly - the entire genome of E.coli has been sequenced and studied for years , hence genetic engineering using E.coli is well understood and there are many tools available such as vectors, promoters, inducers and specified strains. This makes E.coli easy to transform, essentially making this expression system fully customizable! Is it also possible to :

• perform in vitro glycosylation or enzymatic modifications after producing the recombinant proteins

• use affinity tags to increase protein solubility an aid in purification

• use our knowledge of E.coli culture conditions to our advantage eg. lowering incubation temperature to slow growth can aid in proper folding

In comparison, CHO cells are much more difficult to work with. CHO cells require specified bioreactors, expensive culture media and clean rooms to produce recombinant proteins. In addition to this CHO cells give a much poorer yield, have a much longer doubling time ( about 24 hours) and are much more difficult to transform than E.coli cells. CHO cells also don't readily take up recombinant DNA (as eukaryotic cells do not effectively take up plasmids), and aso have the tendency to randomly insert the recombinant DNA into their genome. This can lead to unpredictable expression and yields, and thus makes its use less lucrative for research and experimental purposes.

The Bl21 (DE3) pLysS strain was specifically chosen for this proposed treatment due to its high suitability for recombinant protein production. Bl21 cells lack Lon protease which is responsible for degrading foreign proteins in E.coli cells. Bl21 cells also lack the OmpT membrane protease which degrades extracellular proteins. This prevents digestion of the recombinant proteins produced as well as a loss of plasmid once transformed into the E.coli cells. This strain is therefore highly suitable for expression of recombinant proteins such as L-MAG. Further in vitro modifications as mentioned above could then theoretically produce a safe and effective treatment for MS!

So yes, there are some limitations to using a microbial expression system, compared to a mammalian expression system, but there are many advantages apart from it's cost effectiveness to consider before deciding which expression system to use!

What a clever approach, I really enjoyed this read! I just have one burning question.

With regard to your drug delivery method, I’m interested to know more about why you chose liposome encapsulation as a transfer mechanism; did you also look into any other delivery vesicle?

Would using exosomes, a natural biological vesicle, provide improved transport to the brain? As they are known to have low immunogenetic properties in comparison to liposomes, which are synthetic foreign bodies.

Or do you argue its preference due to its better API protection?

Hi Monica

Thanks for taking the time to read our blog. We looked into a few different delivery methods for L-MAG to reach the brain. As you can imagine, getting it into the body and across the blood-brain barrier is quite the challenge.

While exosomes do have a clear advantage due to their natural makeup, we decided to go with a liposome delivery method.

We felt the liposome would be a good option to protect the L-Mag protein once inside the body, and liked that they are highly stable. The fact that the liposome could be modified with targeting ligands would also give good control over its delivery.