CTE – The Silent Threat

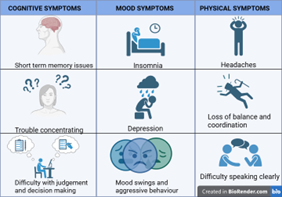

Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, better known as CTE, is a brain disease that develops slowly, but its impact can last a lifetime. CTE was first recognised in boxers during the 1920s, when it was known as “punch-drunk syndrome.” In the years that followed, researchers began to identify similar brain damage in others who had suffered repeated head injuries (Catanese, 2024). In recent years, the modern understanding of CTE has gained significant attention, driven by case studies revealing brain abnormalities found in autopsies of former professional football players (Asken et al., 2016). Researchers estimate that roughly 17% of individuals who experience years of repetitive concussions or mild traumatic brain injuries may develop CTE (Cleveland Clinic, 2022). However, it remains unclear why some people exposed to repeated head impacts develop the disease while others do not. Ongoing research is exploring how genetic, environmental, and lifestyle factors may interact with head trauma to influence the risk of CTE. The effects of CTE on the brain resemble those seen in other forms of dementia, impacting cognitive abilities, mood and personality, and motor function. These symptoms tend to worsen over time, even if no further head injuries occur (Catanese, 2024; Cleveland Clinic, 2022).

Figure 1: Symptoms of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy

Recent research suggests that CTE may be more common in young people than previously thought, especially among those who play contact sports, serve in the military, or experience repeated physical trauma. A study examining the brains of contact sport players who died before age 30 found that over 40% showed signs of CTE (Catanese, 2024). While not everyone with repeated head injuries develops the condition, the risk increases with frequent impacts. The best way to reduce the risk is through prevention, such as wearing proper protective gear and promptly treating any head injuries (NHS, 2019).

Why Current CTE Treatments Fall Short and The Role of Tau Protein

Current treatments for CTE face several challenges. Most of the therapies that are being studied are still in early stages of research and haven’t been proven to be effective in people. Some treatments that target inflammation or aim to protect brain cells work well in animal studies but don’t show the same results in humans. This is because of the way CTE develops in people, especially athletes with repeated head trauma and due to our poor understanding of the complex processes behind it (Breen P.W. & Krishnan V. 2020).

Another issue is that many drugs can’t easily cross the blood-brain barrier, a protective layer that blocks substances from entering the brain. CTE disease also involves complicated processes that happen at the same time, such as brain inflammation, nerve cell damage and oxidative stress, which are hard to fix with just one kind of treatment. Even though some drugs show good results in the lab, they often don’t work as well in real human patients, showing a big gap between lab studies and real-world success. (Donison N. et al. 2025).

Tau is one of the main proteins that cause CTE; it helps to keep the structure of brain cells stable. Acts like a support beam, helping to keep their shape and function properly. Although after repeated head trauma, tau breaks away, changes shape and clumps together between brain cells in harm them. This can be seen in Figure 2, where the tau proteins act as support beams in the healthy nerve cell on the left and on the right side, the tau proteins have built up and become tangled, which damages the nerve cell. These clumps block communication between cells and can lead to cell damage or death (Donison N. et al. 2025).

Figure 2: Representation of Healthy vs Damaged Nerve Cell Showing Tau Protein Changes (Katchur N.J., Notterman D.A. 2024)

This is why finding an effective treatment for CTE is so important. Especially for people in sports or jobs where head injuries happen often. Stopping the damage done by tau protein would improve long-term brain health and patient lives when they get older and must struggle with CTE symptoms.

New Hope: Tau-Targeted Nanoinhibitors

Nanotechnology, a world of tiny particles on a microscale, opens a whole new approach to treating CTE. Nanoparticles are incredibly small particles and are even small enough to have millions that could theoretically fit on the tip of your finger. Scientists are able to engineer the surface of these particles, resulting in a nanoinhibitor that can recognise and bind to tau clumps (Duan et al. 2023).

Traditional drugs usually are unable to cross the brain’s natural protective barrier (blood-brain barrier), but this isn’t a problem for nanoinhibitors. As they evade past this natural protective barrier, they go after their target, in this case tau protein. These nanoinhibitors can also be made multifunctional, meaning these tiny particles can be equipped with other features, such as anti-inflammatory or antioxidant compounds that affect nearby tissue (Jiménez et al. 2025).

Figure 3: Nanoinhibitor vs Traditional drug: Crossing the Blood-Brain Barrier (Created with Biorender.com)

Function of Tau-Nanoinhibitors:

A study released by (Zhu et al. 2021) looked at tau-targeting nanoinhibitors and displayed potential benefits.

The nanoinhibitor's mode of action:

-

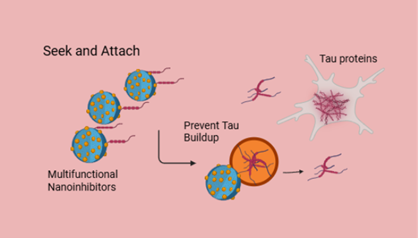

Seeking and Attaching

On the surface of nanoparticles, multiple tiny molecules function as magnets for tau. Once these molecules find tau clumps, they then lock onto them tightly. This process is called multivalent binding, meaning there are many of these molecules on the surface of nanoparticles working together, making it easier and more effective for attaching to tau tangles (Zhu et al. 2021).

-

Prevention of Tau Buildup

As this attachment happens between the nanoinhibitor and tau, other tau proteins are prevented from sticking to the clump. This blocks the growth of the tangle, stopping the spread of misfolded tau in surrounding neurons (Zhu et al. 2021).

-

Facilitate Clearance

After forming a complex with the tau aggregates, it becomes more recognisable for the brain cleanup cells to detect. Studies show that marked tau clumps break down more easily than untagged tau clumps. This means, in easier terms, the nanoinhibitors put a label on toxic debris, making it much easier for the brain to remove (Zhu et al. 2021).

-

Dual Therapeutic Action

Besides targeting tau aggregates, nanoinhibitors can also be designed for more than just a single function. Antioxidants or anti-inflammatory coatings can be added to these nanoparticles to alleviate inflammation and oxidative stress. This extra protection helps cool down overheated brain regions, preventing further harm caused by tau tangles and protecting neurons from secondary damage (Surnar et al. 2018).

As shown in Figure 4 below, nanoparticles attach to tau clumps and prevent their accumulation. This is a promising strategy for treating CTE.

Figure 4: How Nanoinhibitors Stop Tau Buildup in the Brain (Created with Biorender.com)

So far, preliminary studies conducted mostly in cell cultures and animal models suggest that tau-targeted nanoparticles greatly reduce the toxic effects of tau buildup. In one study by (Chen et al. 2018) it was demonstrated that neurons exposed to tau tangles had better survival when nanoinhibitors were present, as fewer cells died and more of them stayed healthy. Although this work is still at an experimental stage, these findings suggest a possible therapy that’s small enough to enter the brain and attack tau and help protect neurons.

Conclusion:

Upcoming research on the use of nanotechnology shows promise for the future. Nano-inhibitors can do wonderful things that regular drugs cannot do currently. They can cross the brain easily, disturbing the accumulated tau clumps that cause damage and remove them. This would result in brain cells being healthier and prevent them from getting worse. More testing would be needed before the treatment can be available worldwide, but it shows a wonderful new way to fight CTE and improve patient lives and those who are at risk in the future.

References:

Asken, B.M., Sullan, M.J., Snyder, A.R., Houck, Z.M., Bryant, V.E., Hizel, L.P., McLaren, M.E., Dede, D.E., Jaffee, M.S., DeKosky, S.T. and Bauer, R.M. (2016). Factors Influencing Clinical Correlates of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE): a Review. Neuropsychology Review, 26(4), pp.340–363. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/s11065-016-9327-z.

Breen P.W. & Krishnan V. (2020). Recent Preclinical Insights Into the Treatment of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy, Texas, United States, Frontiers in Neuroscience, Vol 14, available: https://doi.org/10.3389/fnins.2020.00616.

Catanese, L. (2024). What is CTE? Understanding chronic traumatic encephalopathy. [online] Harvard Health. Available at: https://www.health.harvard.edu/mind-and-mood/what-is-cte-understanding-chronic-traumatic-encephalopathy.

Chen, Q., Du, Y., Zhang, K., Liang, Z., Li, J., Yu, H., Ren, R., Feng, J., Jin, Z., Li, F., Sun, J., Zhou, M., He, Q., Sun, X., Zhang, H., Tian, M., and Ling, D. (2018) “Tau-targeted multifunctional nanocomposite for combinational therapy of Alzheimer’s disease,” ACS nano, 12(2), 1321–1338, available: https://doi.org/10.1021/acsnano.7b07625.

Cleveland Clinic (2022). Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy (CTE) | Cleveland Clinic. [online] Cleveland Clinic. Available at: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/diseases/17686-chronic-traumatic-encephalopathy-cte.

Donison N., Palik J., Volkening K., Strong M.J., (2025). Cellular and molecular mechanisms of pathological tau phosphorylation in traumatic brain injury: implications for chronic traumatic encephalopathy, Canada, PubMed, 20(1)56, available: 10.1186/s13024-025-00842-z.

Duan, L., Li, X., Ji, R., Hao, Z., Kong, M., Wen, X., Guan, F., and Ma, S. (2023) “Nanoparticle-based drug delivery systems: An inspiring therapeutic strategy for neurodegenerative diseases,” Polymers, 15(9), 2196, available: https://doi.org/10.3390/polym15092196.

Jiménez, A., Estudillo, E., Guzmán-Ruiz, M.A., Herrera-Mundo, N., Victoria-Acosta, G., Cortés-Malagón, E.M., and López-Ornelas, A. (2025) “Nanotechnology to overcome blood-brain barrier permeability and damage in neurodegenerative diseases,” Pharmaceutics, 17(3), 281, available: https://doi.org/10.3390/pharmaceutics17030281.

Katchur N.J., Notterman D.A. (2024), Recent insights from non-mammalian models of brain injuries: an emerging literature, United States, ResearchGate, available: 10.3389/fneur.2024.1378620.

NHS (2019). Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy. [online] NHS. Available at: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/chronic-traumatic-encephalopathy/.

Surnar, B., Basu, U., Banik, B., Ahmad, A., Marples, B., Kolishetti, N., and Dhar, S. (2018) “Nanotechnology-mediated crossing of two impermeable membranes to modulate the stars of the neurovascular unit for neuroprotection,” Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America, 115(52), E12333–E12342, available: https://doi.org/10.1073/pnas.1816429115.

Zhu, L., Xu, L., Wu, X., Deng, F., Ma, R., Liu, Y., Huang, F., and Shi, L. (2021) “Tau-targeted multifunctional nanoinhibitor for Alzheimer’s disease,” ACS applied materials & interfaces, 13(20), 23328–23338, available: https://doi.org/10.1021/acsami.1c00257

Add comment

Comments

This was such interesting read! Great idea to try and target the tau tangles with a method that can easily pass the blood brain barrier. A thought I did have while reading this is how could you ensure that the nano particles only target tau tangles and not healthy tau as this could affect brain functionality ?

Great question! Targeting only harmful tau without affecting normal tau is essential. Researchers do this by designing nanoparticles that recognise features found only in diseased tau, such as its abnormal shape (misfolded/hyperphosphorylated), large aggregates, not single healthy tau proteins, and disease-specific chemical changes, extracellular tau, which healthy tau normally isn’t.

These differences act like a “signature,” allowing nanoparticles to bind toxic tau while leaving normal tau untouched.

Your blog has nicely illustrated the potential of nano-inhibitor in repairing the tau-related damage, but we need more studies to define the function of nanotechnology and still uncertainty remains how these nano-inhibitors show long term impact in the brain and their longterm stay in the brain.

You’re absolutely right — while nano-inhibitors show promising early results, we still don’t fully understand their long-term behaviour in the brain. Most current studies are short-term and done in cell models or animals, so questions remain about how long nanoparticles stay in brain tissue, how they break down, and whether they could cause inflammation or other effects over time. More long-term safety studies and human trials will be essential before we can know their full impact.

This was a very interesting read, I learnt a lot! I do wonder though, what regulation hurdles researchers will be faced with when trying to get this to human clinical trials?