Introduction

Tackles, punches, falls, they are all a part of sport. However, what might seem like innocent and harmless events can have devastating consequences. Chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) is a progressive neurodegenerative condition caused by repetitive head trauma. It results in cognitive and mood-related symptoms, including memory loss, confusion, and depression. CTE affects a diverse group of people across various sports. One study of 152 brain samples from young athletes who had experienced repetitive head injuries found that 41.4% had CTE (McKee et al., 2013). Yet, current treatments only aim to manage symptoms, rather than prevent or cure the disease itself. It's important to develop therapies that can stop the disease at its root cause so athletes, both young and old, can continue to pursue their passions safely. So, how do we “tackle” this problem?

What Causes CTE?

CTE is caused by the abnormal clumping of the protein tau (McKee et al., 2015). Tau is responsible for maintaining the structural integrity of neurons and allows the transport of molecules along the cell. When tau becomes hyperphosphorylated, it clumps together to form aggregates in the brain, which damage and kill neurons, leading to the neurodegeneration seen in CTE.

PPP3CA is a part of calcineurin, a protein that maintains tau in a normal, healthy form by removing phosphate groups from it (Castiglioni et al., 2024). Studies have shown that in both traumatic brain injury (TBI) and CTE, levels of PPP3CA are reduced. For example, Seo et al., 2017, found that PPP3CA was lower in CTE brain samples at both the gene and protein level when compared to healthy samples. In animal studies, researchers found that decreased levels of PPP3CA in the frontal cortex were correlated with an increased level of hyperphosphorylated tau (Seo et al., 2017)

These findings suggest that the hyperphosphorylation of tau seen following TBI and in CTE may be at least partly due to the reduction in PPP3CA. Therefore, increasing PPP3CA expression in neurons could prevent or reverse tau hyperphosphorylation, potentially stopping the aggregation that results in neurodegeneration. Not only could this approach be used to slow the progression of existing CTE, but if given soon after TBI, it may prevent the development of CTE.

Novel Therapy

To achieve increased expression of PPP3CA, I propose using dCas9-VPR, a technique previously utilised to upregulate gene expression in the brain (Savell et al., 2019). First, a single guide RNA (sgRNA) is designed to target and bind to the region of the PPP3CA gene that controls gene expression by deciding when a gene is switched on. The dCas9-VPR system consists of two parts: the VPR activation domain that binds to the target gene and recruits transcriptional activators to switch on the gene, and an inactive form of the Cas9 enzyme that acts as a scaffold to help hold the VPR domain in place on the gene (Chen and Qi, 2017).

To deliver these components to neurons, they are packaged into split-intein dual AAV vectors (Böhm et al., 2020). AAV vectors are harmless forms of viruses capable of delivering genes into cells. Using dual AAV vectors overcomes the size limit of a single AAV and allows them to cross the blood-brain barrier. The dCas9-VPR protein is split into two halves, one with the N-terminal, i.e. the start of the protein, and one with the end of the protein, the C-terminal. Each half is fused to an intein, a small protein that can join two other protein segments. The IntN intein is fused to the N-terminal half, and IntC is fused to the C-terminal half.

Two AAV vectors are then made:

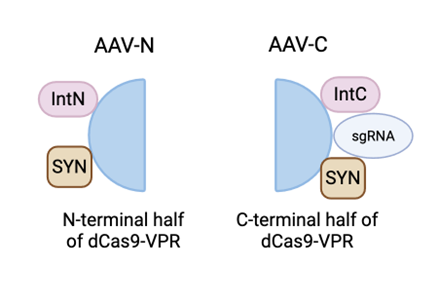

AAV-N; contains the N-terminal half of dCas9-VPR fused with IntN and a neuron-specific promoter, SYN, to guide the vectors into neurons.

AAV-C; contains the C-terminal half of dCas9-VPR fused with IntC, the same neuron promoter, SYN, and the sgRNA.

Figure 1: The components of AAV-N and AAV-C

The two vectors are produced in HEK293 cells, a human cell line that can be grown in a lab. Three DNA plasmids are introduced into the HEK293 cells: the transgene plasmid containing the AAV components, a helper plasmid, and a rep/cap plasmid (She et al., 2023). The rep/cap plasmid makes the outer shell of the vectors from serotype 9 proteins, which allows them to cross into the brain. The HEK293 cells now containing these three plasmids are grown to produce large amounts of the AAV vectors. The vectors are then purified to isolate them from the cells and can be administered via IV infusion.

Once both vectors enter the same neuron, the components in each vector are made into two protein halves of the dCas9-VPR protein. The inteins bound to each half recognise each other and cause trans-splicing, which fuses the protein halves into one, full-length protein (Tornabene et al., 2019). The inteins will be removed from the protein automatically. The sgRNA binds to and guides the full-length dCas9-VPR protein to the PPP3CA gene. The VPR activation domain binds to the promoter region of the gene and initiates gene transcription by recruiting transcriptional machinery, including transcription factors and RNA polymerase II (Chavez et al., 2015). The activation of gene transcription allows more mRNA to be created, which can then go on to make more of the PPP3CA protein.

Figure 2: The dCas9-VPR System

Conclusion

By targeting the root cause of tau accumulation, increasing PPP3CA expression could provide a novel approach to tackling CTE. Using the dCas9-VPR system delivered to neurons via dual AAV vectors, it may be possible to reduce tau phosphorylation and prevent the harmful aggregation that leads to neurodegeneration. Instead of aiming only to manage symptoms, this approach could stop CTE from worsening or could prevent it from occurring. This could be a game-changer for athletes, allowing them to continue engaging in sports without the worry of the long-term impacts of this devastating condition.

References:

Böhm, S., Splith, V., Riedmayr, L.M., Rötzer, R.D., Gasparoni, G., Nordström, K.J.V., Wagner, J.E., Hinrichsmeyer, K.S., Walter, J., Wahl-Schott, C., Fenske, S., Biel, M., Michalakis, S. and Becirovic, E. (2020). A gene therapy for inherited blindness using dCas9-VPR–mediated transcriptional activation. Science Advances, 6(34), p.eaba5614. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/sciadv.aba5614.

Castiglioni, S., Pezzoli, L., Pezzani, L., Lettieri, A., Fede, E.D., Cereda, A., Ancona, S., Gallina, A., Colombo, E.A., Parodi, C., Grazioli, P., Esi Taci, Milani, D., Iascone, M., Massa, V. and Gervasini, C. (2024). Expanding the clinical spectrum of PPP3CA variants - alternative isoforms matter. Orphanet Journal of Rare Diseases, 19(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1186/s13023-024-03507-0.

Chavez, A., Scheiman, J., Vora, S., Pruitt, B.W., Tuttle, M., P R Iyer, E., Lin, S., Kiani, S., Guzman, C.D., Wiegand, D.J., Ter-Ovanesyan, D., Braff, J.L., Davidsohn, N., Housden, B.E., Perrimon, N., Weiss, R., Aach, J., Collins, J.J. and Church, G.M. (2015). Highly efficient Cas9-mediated transcriptional programming. Nature Methods, 12(4), pp.326–328. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/nmeth.3312.

Chen, M. and Qi, L.S. (2017). Repurposing CRISPR System for Transcriptional Activation. Advances in experimental medicine and biology, 983, pp.147–157. doi:https://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-10-4310-9_10.

McKee, A.C., Mez, J., Bobak Abdolmohammadi, Butler, M., Bertrand Russell Huber, Uretsky, M., Babcock, K., Cherry, J.D., Alvarez, V.E., Martin, B., Yorghos Tripodis, Palmisano, J.N., Cormier, K.A., Kubilus, C.A., Nicks, R., Kirsch, D., Mahar, I., McHale, L., Nowinski, C. and Cantu, R.C. (2023). Neuropathologic and Clinical Findings in Young Contact Sport Athletes Exposed to Repetitive Head Impacts. JAMA Neurology, 80(10). doi:https://doi.org/10.1001/jamaneurol.2023.2907.

McKee, A.C., Stein, T.D., Kiernan, P.T. and Alvarez, V.E. (2015). The Neuropathology of Chronic Traumatic Encephalopathy. Brain Pathology, 25(3), pp.350–364. doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/bpa.12248.

Savell, K.E., Bach, S.V., Zipperly, M.E., Revanna, J.S., Goska, N.A., Tuscher, J.J., Duke, C.G., Sultan, F.A., Burke, J.N., Williams, D., Ianov, L. and Day, J.J. (2019). A Neuron-Optimized CRISPR/dCas9 Activation System for Robust and Specific Gene Regulation. Eneuro, 6(1), pp.ENEURO.0495-18.2019. doi:https://doi.org/10.1523/eneuro.0495-18.2019.

Seo, J.S., Lee, S., Shin, J.Y., Hwang, Y.J., Cho, H., Yoo, S.K., Kim, Y., Lim, S., Kim, Y.K., Hwang, E.M., Kim, S.H., Kim, C.H., Hyeon, S.J., Yun, J.Y., Kim, J., Kim, Y., Alvarez, V.E., Stein, T.D., Lee, J. and Kim, D.J. (2017). Transcriptome analyses of chronic traumatic encephalopathy show alterations in protein phosphatase expression associated with tauopathy. Experimental & Molecular Medicine, 49(5), pp.e333–e333. doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/emm.2017.56.

She, K., Liu, Y., Zhao, Q., Jin, X., Yang, Y., Su, J., Li, R., Song, L., Xiao, J., Yao, S., Lu, F., Wei, Y. and Yang, Y. (2023). Dual-AAV split prime editor corrects the mutation and phenotype in mice with inherited retinal degeneration. Signal Transduction and Targeted Therapy, 8(1). doi:https://doi.org/10.1038/s41392-022-01234-1.

Tornabene, P., Trapani, I., Minopoli, R., Centrulo, M., Lupo, M., de Simone, S., Tiberi, P., Dell’Aquila, F., Marrocco, E., Iodice, C., Iuliano, A., Gesualdo, C., Rossi, S., Giaquinto, L., Albert, S., Hoyng, C.B., Polishchuk, E., Cremers, F.P.M., Surace, E.M. and Simonelli, F. (2019). Intein-mediated protein trans-splicing expands adeno-associated virus transfer capacity in the retina. Science translational medicine, 11(492), p.eaav4523. doi:https://doi.org/10.1126/scitranslmed.aav4523.

Add comment

Comments

Thank for an interesting blog! I was thinking if there is any side effect in increasing PPP3CA expression in the neurons? As PPP3CA is a part of different signalling pathways.

Also, you write that "PPP3CA is a part of calcineurin, a protein that maintains tau in a normal, healthy form by removing phosphate groups from it." Could an increased PPP3CA expression result in removal of all phosphate groups from tau? Which I imagine, would be critical for microtubules stabilization.

Hi Sofie,

You make a really good point, and the risk of side effects is definitely something that would need to be taken into account. As for the dephosphorylation of tau, I don’t think increasing PPP3CA expression would remove all phosphates from it. There are many phosphatases that remove phosphate groups from different regions of tau, such as PP2A and PP1. PP2A alone is responsible for 71% of total tau phosphatase activity in neurons (Liu et al., 2005), meaning the majority of the tau protein would not be affected by an increase in calcineurin activity. Because of this, it would be unlikely that tau would completely dissociated from microtubules and cause them to become destabilised. However, I do suspect there could be side effects of increasing PPP3CA expression. Some studies have shown that PPP3CA gain-of-function mutations can cause seizures (Mizuguchi et al., 2018), so this would have to be assessed before treating patients with a PPP3CA upregulator. Also, because calcineruin has many roles in neurons, increasing it could alter these functions. For example, overactivity of calcineurin could lead to impaired synaptic plasticity due to the inability for neurons to undergo long term potentiation. These are all very important factors that would need to be further investigated before any treatments are developed.

References:

Liu, F., Grundke-Iqbal, I., Iqbal, K., & Gong, X. (2005). Contributions of protein phosphatases PP1, PP2A, PP2B and PP5 to the regulation of tau phosphorylation. European Journal of Neuroscience, 22(8), 1942-1950. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1460-9568.2005.04391.x

Mizuguchi, T., Nakashima, M., Kato, M., Okamoto, N., Kurahashi, H., Ekhilevitch, N., Shiina, M., Nishimura, G., Shibata, T., Matsuo, M., Ikeda, T., Ogata, K., Tsuchida, N., Mitsuhashi, S., Miyatake, S., Takata, A., Miyake, N., Hata, K., Kaname, T., . . . Matsumoto, N. (2018). Loss-of-function and gain-of-function mutations in PPP3CA cause two distinct disorders. Human Molecular Genetics, 27(8), 1421-1433. https://doi.org/10.1093/hmg/ddy052