Picture this, you’re living the best years of your life. You’re energetic, vibrant and determined to hold onto your youth. Then you begin to lose your hair, with society having you believe this is the end. Desperate for a solution you search for medical guidance. It appears all hope is not lost. Your doctor prescribes you with what seems like a miracle drug: Finasteride. The drug promises to halt your hair loss with little or no side effects.

This isn’t the case for you. It starts with a decreased libido, then anxiety, brain fog quickly follows and before long you are battling depression. Logically, after six months of this, you decide to stop taking the medication, expecting your body and mood to return to normal.

For some however, this is not the case. Sufferers of Post Finasteride Syndrome (PFS) report persistent symptoms, sometimes lasting months or even years after discontinuation (Traish, 2020).

The question is, why?

Let us first look at why hair loss occurs. The driving force behind androgenic alopecia, better known as male or female pattern baldness, is a hormone called DHT, short for dihydrotestosterone. DHT is formed when the enzyme 5α-reductase converts testosterone into a more potent version of itself (Cleveland Clinic, 2022). DHT binds androgen receptors with a fourfold higher affinity than testosterone (Swerdloff et al., 2017), leading to hair follicle miniaturisation, producing thinner and weaker hair until the hairs eventually stop growing.

Figure 1: The conversion of testosterone to DHT by 5-α-reductase. Made using BioRender.

Finasteride is a 5α-reductase inhibitor that blocks the type II isoenzyme responsible for converting testosterone to DHT (Melcangi et al., 2017). This leads to reduced levels of DHT in the scalp which significantly slows the rate of hair loss progression. Finasteride is a competitive inhibitor of the 5α-reductase enzyme meaning it binds to the active site of the enzyme and prevents its normal substrate testosterone from binding. Finasteride has a greater affinity for the type II isoenzyme however it has been shown to also bind the type I isoenzyme (Melcangi et al, 2017), which will be relevant to the side effects we will explore next.

Figure 2: Competitive inhibition of 5-α-reductase by Finasteride. Made using BioRender..

Now that we have established this basis let us look at why side effects may occur. 5α-reductase is found everywhere in the body, and the inhibition of this enzyme within the brain could potentially play a major factor in the persistent psychological symptoms.

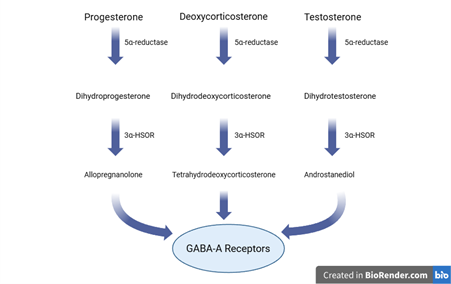

Neurosteroids are chemicals in the brain that work to stabilise emotional responses such as stress and anxiety (Reddy, 2010). Figure 3 depicts the synthesis of the three neurosteroids that rely on 5α-reductase for synthesis (MacKenzie and Maguire, 2013). Inhibition of this enzyme could result in decreased levels of the neurosteroids allopregnanolone, tetrahydrodeoxycorticostrone and androstanediol.

Figure 3: Neurosteroid syntheses that may be affected by inhibition of 5α-reductase enzyme. Made using BioRender.

Allopregnanolone is an important neurosteroid. Its main functions are to produce calming and sleep-inducing effects, reduce anxiety and seizures, helping the body manage stress and supporting brain cell protection (Diviccaro et al., 2022). Allopregnanolone synthesis relies on the type I isoenzyme of 5α-reductase. As we have seen, while Finasteride has a higher affinity for the type II isoenzyme it is suspected that inhibition of the type I isoenzyme can also occur (Melcangi, 2017).

Allopregnanolone is involved in the GABAergic pathway alongside the neurotransmitter Gamma-aminobutyric acid (GABA), which helps the body to relax and maintain emotional balance (Belelli et al., 2022).

In this pathway, neurons communicate by releasing neurotransmitters across synapses, the gaps between communicating cells. When GABA is released from a neuron it binds to GABA-A receptors on the next cell, opening channels that let negatively charged chloride ions flow in. This hyperpolarizes the neuron.

For a neuron to send a signal, it must become depolarised. Therefore, when GABA causes chloride ions to enter the neuron, it makes the neuron less likely to fire. This inhibitory effect of GABA on neuronal signalling produces a calming and relaxing influence on the brain.

Neurosteroids, such as allopregnanolone enhance this process by binding to GABA-A receptors, which results in the receptor staying open for longer, allowing more chloride ions to enter the cell, increasing the duration of the calming effect (Paul and Purdy, 1992).

Figure 4: Schematic representation of the GABAergic pathway with neurosteroid modulation of GABA-A receptors. Made using BioRender.

We therefore propose the decrease in neurosteroid levels due to the inhibition of 5α-reductase as a possible cause of the neurological side effects of Finasteride. This is supported by research done by Mukai et al measuring neurosteroid levels in rats who received Finasteride. The findings of this study saw that rats who were administered 10 mg/kg of finasteride showed a near complete depletion of allopregnanolone in the brain (Mukai et al., 2008).

While this may explain the initial cause of neurological symptoms it is also important to search for answers to the question of why symptoms persist. Giatti et al have studied the effects of sub chronic finasteride treatment at low doses (3 mg/kg/day) and withdrawal on neuroactive steroid levels and their receptors in the male rat brain. Findings of this study showed that levels of dihydroprogesterone (DHP), the precursor to allopregnanolone were decreased in the cerebral cortex after Finasteride withdrawal (Giatti et al., 2016). Interestingly the study found that the effects of Finasteride withdrawal were stronger than the effects of Finasteride treatment at this dose in male rat brains. The authors suggest that the steroidogenic system can partially adapt and compensate for the chronic inhibition of 5α-reductase activity. However, after this adaptation, the system may be less flexible to compensate for a new alteration.

A study conducted by Melcangi et al found after analysing methylation patterns on the genes that encode for the 5α-reductase enzyme, the SRD5A2 promoter gene was more frequently methylated in the CSF of PFS patients compared to controls, 56.3 vs 7.7% (Melcangi et al, 2019). As SRD5A2 encodes for the type II isoenzyme, it is suggested that the methylation-induced silencing of SRD5A2 in the CNS could lead to persistent reductions in neuroactive steroids.

So, how do we treat these symptoms? The first logical response when a patient is suffering from depression or anxiety would be to treat the patient with antidepressants, notably SSRIs. This may help with the depression and anxiety, but a common side effect of SSRIs is sexual dysfunction, from which PFS patients may already suffer. There’s no point treating one symptom with the potential of worsening another symptom, right? In this case, it’s time to think outside the box, and look at the information above to find a novel therapeutic.

Finasteride decreases allopregnanolone, so theoretically we could resolve this issue by replenishing allopregnanolone levels in the body. While the research into PFS is lacking, research on post-partum depression (PPD) is well established. The GABAergic signalling hypothesis in PPD proposes that during pregnancy, levels of neurosteroids such as allopregnalone rise dramatically but after delivery neurosteroid levels drop sharply (Meltzer-Brody and Kanes, 2020). This drop leads to symptoms of PPD such as anxiety, depression and mood instability. Sounds familiar?

The exciting news is that there are successful treatments for PPD that target GABA-A receptor modulation. Brexanolone, an aqueous formulation of allopregnanolone (Azhar and Din, 2023), is an FDA-approved medication for PPD that has demonstrated rapid and promising results. It works by enhancing GABA-A receptor activity, mimicking the action of endogenous allopregnanolone.

While intravenous Brexanolone may not be the most convenient option for patients, a new oral medication, Zuranolone, received FDA approval in 2023 for PPD. Zuranolone is not an oral form of allopregnanolone, but it is a GABA-A receptor positive allosteric modulator. It modulates both synaptic and extra synaptic GABA-A receptors (Patterson et al., 2023), which could theoretically help restore GABAergic signaling in patients with PFS.

The side effects of both medications are generally limited to drowsiness. Although these medications are currently only approved for use in women, there is no obvious biological reason they should be poorly tolerated in men, suggesting a potential avenue for future research into the treatment of PFS.

To conclude, finasteride is causing a wide range of issues within the body. While the syndrome requires further investigation this offers an insight into one of the potential causes of persistent symptoms and a possible course of treatment for the future.

References

Azhar, Y. and Din, A.U. (2023) ‘Brexanolone’, in StatPearls [Internet]. Treasure Island (FL): StatPearls Publishing. Available at: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK541054/

Belelli, D., Peters, J.A., Phillips, G.D. and Lambert, J.J. (2022). The immediate and maintained effects of neurosteroids on GABAA receptors. Current Opinion in Endocrine and Metabolic Research, 24, p.100333. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.coemr.2022.100333

Cleveland Clinic. (2022) DHT (Dihydrotestosterone): What It Is, Side Effects & Levels. Cleveland Clinic. Available at: https://my.clevelandclinic.org/health/articles/24555-dht-dihydrotestosterone (Accessed: 20 October 2025).

Diviccaro, S., Cioffi, L., Falvo, E., Giatti, S. and Melcangi, R.C. (2022) ‘Allopregnanolone: An overview on its synthesis and effects’, Journal of Neuroendocrinology, 34(2), e12996. doi: 10.1111/jne.12996.

Diviccaro, S., Giatti, S., Cioffi, L., Falvo, E., Herian, M., Caruso, D. and Melcangi, R.C. (2022) ‘Gut inflammation induced by finasteride withdrawal: therapeutic effect of allopregnanolone in adult male rats’, Biomolecules, 12(11), p. 1567. doi: 10.3390/biom12111567.

Giatti, S., Foglio, B., Romano, S., Pesaresi, M., Panzica, G., Garcia-Segura, L.M., Caruso, D. and Melcangi, R.C. (2016) ‘Effects of subchronic finasteride treatment and withdrawal on neuroactive steroid levels and their receptors in the male rat brain’, Neuroendocrinology, 103(6), pp. 746–757. doi: 10.1159/000442982.

MacKenzie, G. and Maguire, J. (2013). Neurosteroids and GABAergic signaling in health and disease. BioMolecular Concepts, 4(1), pp.29–42. doi:https://doi.org/10.1515/bmc-2012-0033.

Melcangi, R.C., Casarini, L., Marino, M., Santi, D., Sperduti, S., Giatti, S., Diviccaro, S., Grimoldi, M., Caruso, D., Cavaletti, G. and Simoni, M. (2019) ‘Altered methylation pattern of the SRD5A2 gene in the cerebrospinal fluid of post-finasteride patients: a pilot study’, Endocrine Connections, 8(8), pp. 1118–1125. doi: 10.1530/EC-19-0199.

Melcangi, R.C., Santi, D., Spezzano, R., Grimoldi, M., Tabacchi, T., Fusco, M.L., Diviccaro, S., Giatti, S., Carrà, G., Caruso, D., Simoni, M. & Cavaletti, G. (2017) ‘Neuroactive steroid levels and psychiatric and andrological features in post‑finasteride patients’, Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 171, pp. 229–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2017.04.003.

Meltzer-Brody, S. and Kanes, S.J. (2020). Allopregnanolone in postpartum depression: Role in pathophysiology and treatment. Neurobiology of Stress, 12, p.100212. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ynstr.2020.100212.

Mukai, Y., Higashi, T., Nagura, Y. & Shimada, K. (2008) ‘Studies on neurosteroids XXV. Influence of a 5α‑reductase inhibitor, finasteride, on rat brain neurosteroid levels and metabolism’, Biological & Pharmaceutical Bulletin, 31(9), pp. 1646–1650. doi: 10.1248/bpb.31.1646.

Patterson, R., Balan, I., Morrow, A.L. & Meltzer‑Brody, S. (2023) ‘Novel neurosteroid therapeutics for post‑partum depression: perspectives on clinical trials, program development, active research, and future directions’, Neuropsychopharmacology, 49(1), pp. 67‑72. doi: 10.1038/s41386‑023‑01721‑1.

Paul, S.M. and Purdy, R.H., 1992. Neuroactive steroids. The FASEB Journal, 6(6), pp.2311–2322. https://doi.org/10.1096/fasebj.6.6.1347506

Reddy, D.S. (2010) ‘Neurosteroids: endogenous role in the human brain and therapeutic potentials’, Progress in Brain Research, 186, pp. 113–137. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-444-53630-3.00008-7.

Swerdloff, R.S., Dudley, R.E., Page, S.T., Wang, C. & Salameh, W.A. (2017) ‘Dihydrotestosterone: Biochemistry, Physiology, and Clinical Implications of Elevated Blood Levels’, Endocrine Reviews, 38(3), pp. 220–254. doi:10.1210/er.2016‑1067.

Traish, A.M. (2020). Post-finasteride syndrome: a surmountable challenge for clinicians. Fertility and Sterility, [online] 113(1), pp.21–50. doi:https://doi.org/10.1016/j.fertnstert.2019.11.030.

Add comment

Comments

This is such an interesting post. The way you connect/ point out the similarities between PFS and PPD made it very easy to see how this could be a realistic option for treatment in the near future. It made me consider how the existing PPD treatments would have to be modified to treat men with PFS. I would assume dosing and treatment duration would be some of the main changes. Would hormone differences also play a role in deciding what modifications need to occur?

Thank you for feedback Mairéad! This is a great point yes. Currently there is little to no information on the use of Brexanolone in men as there was no need to collect this data for PPD. I would also agree dosing would be a main change. The point of hormone differences is challenging to answer without any data however if we assume that the men with PFS are experiencing a drop in allopregnanolone and either drug only has the target of mimicking allopregnanolone's effect in the body, without the need for modifications, that there shouldn't be a difference in it's effectiveness in men or women. Please let me know your thoughts on this too!

Really nice blog. So easy to read. Lovely progression from pathological process to possible treatment targets.

I have one question. It states, “Allopregnanolone synthesis relies on the type I isoenzyme of 5α-reductase.” Is type 1 isoenzyme as important as type 2 and 3 when considering the neurological side effects associated with PFS?

Yamana et al showed that the mRNA expression levels of type 3 isoenzyme where much higher than type 1 and 2, in 20 tissue types, including the brain. They also demonstrated that type 2 and 3 had similar sensitivity to finasteride.

Abstract page 293: Yamana K et al. (2010) Human type 3 5α-reductase is expressed in peripheral tissues at higher levels than types 1 and 2 and its activity is potently inhibited by finasteride and dutasteride. Hormone Molecular Biology and Clinical Investigation. 2(3): 293-299.

Hi Wesley, we are happy to hear that the blog was easy to read. We focused on type I of the isoenzyme because of its role in allopregnanolone synthesis. When researching allopregnanolone we noticed its importance in post-partum depression and wanted to understand if decreased levels of this neurosteroid could relate to the psychological effects reported in PFS. We wanted to concentrate on this pathway and its potential treatment to keep our blog concise. However, it would be interesting to explore and understand further what is happening when the other isoenzymes are inhibited. Type 2 is involved in DHT synthesis and type 3 is involved in glycosylation of proteins. Inhibition of type 2 could be causing disruption of androgenic and neurochemical pathways. Inhibition of type 3 could be causing disruption in protein glycosylation, which could also contribute to changes/disruptions in neurological function. Thank you for your comment and it is an interesting area to investigate further!