Jane Smith (a pseudonym to protect her identity), was diagnosed with Multiple Sclerosis (MS) as a young woman, but by the time she was pregnant with her first child, it was well-controlled through medication. The medication she was on, Aubagio, was not safe for a developing fetus nor a breastfeeding child, so she was forced to discontinue her medication for the duration of the pregnancy and post-partum breastfeeding period. Despite this, her pregnancy was uneventful with no relapses of her MS, but shortly after she started breastfeeding her newborn baby her symptoms resumed in earnest. Had breastfeeding somehow made her MS worse? Jane had to resume her medication after breastfeeding for only one month, despite preferring to continue breastfeeding.

To answer whether breastfeeding made Jane experience an MS relapse, we first need to get a better understanding of MS. MS is an autoimmune disease that is not fully understood and is hotly debated in the scientific world, but it certainly involves immune cells making their way into the brain and attacking the fatty insulating sheaths that make our brain cells—neurons—conduct signals quickly between regions of the brain.1 Why these immune cells are crossing the blood-brain barrier, which normally prevents this from occurring, and why they are primed towards targeting the myelin sheaths is not well understood. Once one of these immune cell attacks occur, the damage to that region of the brain can be long-lasting and extensive, leading to scarring and long-term partial loss of function for that area, or it can largely resolve to pre-relapse levels.1

Generally, instances of immune cells crossing; causing damage, inflammation, and scarring; and then quieting down coincide with clinical events where patients experience a surge of symptoms that we call relapses. These relapses represent debilitating but temporary loss of function while the brain is inflamed, that then largely resolves after a period, ranging between 24-hours to around 4 weeks.1 Relapses are the hallmark of Relapsing-Remitting MS, which is standard form of MS, and have been involved in the clinical diagnostic criteria since its first description by Charcot in 1868.2 Relapses are also the clinical target of most MS medications. In fact, the most potent medications on the market today are associated with almost no relapses in patients.3,4

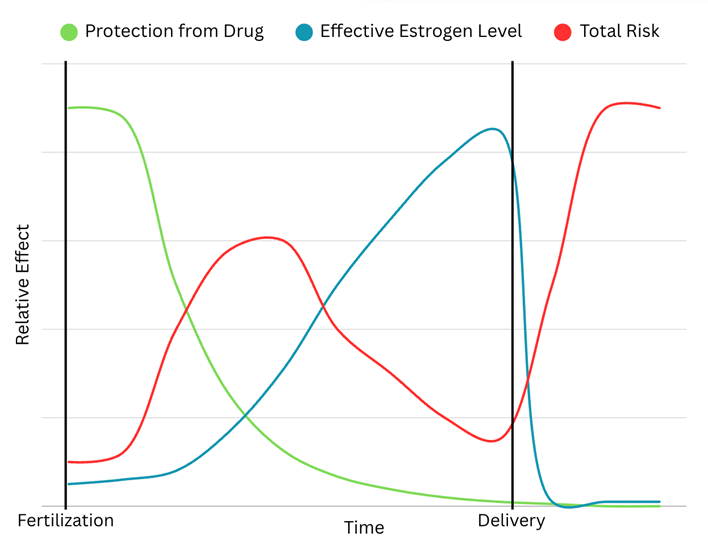

Jane, having been off her medication for the duration of her pregnancy, was certainly no longer under its protective effect, but the timing of the symptom worsening is still suspicious. Why did her symptoms get so much worse only after she started breastfeeding?

The first possibility to rule out is an Aubagio-rebound syndrome. This is a phenomenon that is not well documented, but a few doctors have reported cases of individual patients experiencing significant worsening of their MS shortly after discontinuing Aubagio.5-7 However, even the doctors reporting these instances question whether they are truly a worsening following the cessation of the drug or whether there are other factors influencing this. Additionally, in most rebound syndromes, we would expect to see the effect within 24 weeks, significantly shorter than the ninth months that Jane was off medication for.

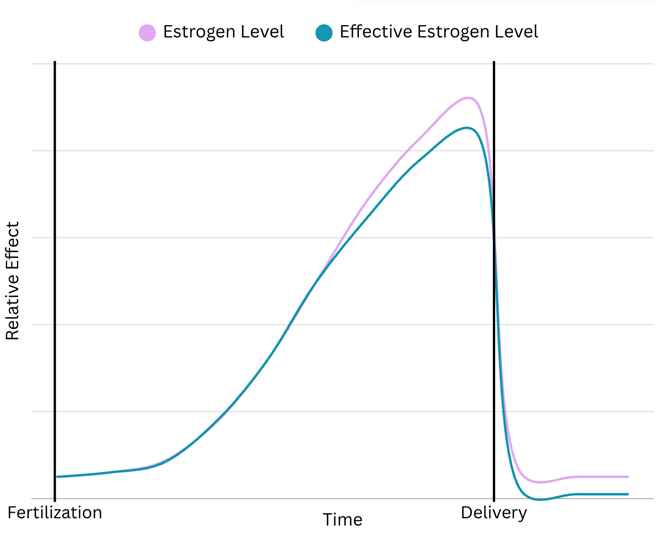

A potentially novel alternative focuses more on the role hormones play in MS. During pregnancy, women produce continually increasing levels of estrogen which suddenly drop following delivery.8 During this time, it is entirely feasible that the pregnant mother slowly experiences a degree of estrogen desensitization, where her body stops responding as directly to the presence of estrogen. Desensitization is a general term for the process where something, be it a body or a receptor, becomes less sensitive to a stimulus over time.9,10 You experience desensitization if you walk into a room that smells unpleasant, but 15 minutes later you don’t even notice the smell. This process applies over a range of timescales and systems, but in the case of a hormone receptors, several weeks at elevated levels would be enough to downregulate the receptors.11 Unfortunately, that timeline lines up closely with pregnancy, and after estrogen levels return to normal following delivery, the fact that Jane could have been desensitized to estrogen means that the normal levels of estrogen were likely not causing the normal level of response from her body. In other words, while Jane may have had normal levels of estrogen in her bloodstream, her body would have been acting like the levels of estrogen were much lower than normal.

To understand why this is important, we must focus on the estrogen’s role as a protective factor for MS symptoms. In fact, while women are much more likely to develop MS, their prognosis is much better than a demographically matched man1,12 Additionaly, although studies in humans for this are challenging, there is plenty of evidence in mice that estrogen directly correlates with less disease activity, correlating nicely with the decreased disease activity we observe during pregnancy.13-15 Therefore, if estrogen is protective against relapses, and Jane’s body was operating as if she had lower than normal levels of estrogen, then she underwent a period of increased susceptibility to MS relapses directly after delivery. This is actually further supported by the increase in relapses immediately following delivery for many with MS.13 With all that in mind, it is not surprising that she had relapses in that period where she had no protection from the drug and an increased risk of relapse.

Jane being forced to stop breastfeeding and resume treatment was not inevitable, though, and if she were to have a child today, best practices would hopefully keep her safe from a similar outcome. Many modern medications are much safer for breastfeeding, and best practices involve resuming treatment during the breastfeeding period to better protect the mother from this period of increased susceptibility.16 Today, mothers like Jane do not have to choose between breastfeeding their child or staying on treatment, as long as they plan ahead and prepare a treatment plan when they begin trying. Of course, as always, if you believe this applies to you, consult with your physician before making any major treatment decisions.

References

1 Hernandez, A. L., O’Connor, K. C. & Hafler, D. A. in The Autoimmune Diseases (Fifth Edition) (eds Noel R. Rose & Ian R. Mackay) 735-756 (Academic Press, 2014).

2 biologie, S. d. Comptes rendus des séances et mémoires de la Société de biologie. (Au Bureau de la Gazette médicale, 1870).

3 Roos, I. et al. Rituximab vs Ocrelizumab in Relapsing-Remitting Multiple Sclerosis. JAMA Neurol 80, 789-797 (2023). https://doi.org:10.1001/jamaneurol.2023.1625

4 Samjoo, I. A. et al. Comparative efficacy of therapies for relapsing multiple sclerosis: a systematic review and network meta-analysis. J Comp Eff Res 12, e230016 (2023). https://doi.org:10.57264/cer-2023-0016

5 Fuerte-Hortigon, A. et al. Rebound after discontinuation of teriflunomide in patients with multiple sclerosis: 2 case reports. Mult Scler Relat Disord 41, 102017 (2020). https://doi.org:10.1016/j.msard.2020.102017

6 Labauge, P., Ayrignac, X., Prin, P., Charif, M. & Carra-Dalliere, C. Rebound syndrome in two cases of MS patients after teriflunomide cessation. Acta Neurol Belg 122, 1381-1384 (2022). https://doi.org:10.1007/s13760-022-01929-w

7 Yamout, B. I. et al. Rebound syndrome after teriflunomide cessation in a patient with multiple sclerosis. J Neurol Sci 380, 79-81 (2017). https://doi.org:10.1016/j.jns.2017.07.014

8 Jee, S. B. & Sawal, A. Physiological changes in pregnant women due to hormonal changes. Cureus 16, e55544 (2024). https://doi.org:10.7759/cureus.55544

9 Field, M., Dorovykh, V., Thomas, P. & Smart, T. G. Physiological role for GABAA receptor desensitization in the induction of long-term potentiation at inhibitory synapses. Nature Communications 12, 2112 (2021). https://doi.org:10.1038/s41467-021-22420-9

10 Mrug, S., Madan, A., Cook, E. W., 3rd & Wright, R. A. Emotional and physiological desensitization to real-life and movie violence. J Youth Adolesc 44, 1092-1108 (2015). https://doi.org:10.1007/s10964-014-0202-z

11 Rajagopal, S. & Shenoy, S. K. GPCR desensitization: Acute and prolonged phases. Cell Signal 41, 9-16 (2018). https://doi.org:10.1016/j.cellsig.2017.01.024

12 Coyle, P. K. What can we learn from sex differences in MS? J. Pers. Med. 11, 1006 (2021). https://doi.org:10.3390/jpm11101006

13 Confavreux, C., Hutchinson, M., Hours, M. M., Cortinovis-Tourniaire, P. & Moreau, T. Rate of pregnancy-related relapse in multiple sclerosis. Pregnancy in Multiple Sclerosis Group. N Engl J Med 339, 285-291 (1998). https://doi.org:10.1056/NEJM199807303390501

14 Bodhankar, S., Wang, C., Vandenbark, A. A. & Offner, H. Estrogen-induced protection against experimental autoimmune encephalomyelitis is abrogated in the absence of B cells. Eur. J. Immunol. 41, 1165-1175 (2011). https://doi.org:10.1002/eji.201040992

15 Santana-Sanchez, P., Vaquero-Garcia, R., Legorreta-Haquet, M. V., Chavez-Sanchez, L. & Chavez-Rueda, A. K. Hormones and B-cell development in health and autoimmunity. Front Immunol 15, 1385501 (2024). https://doi.org:10.3389/fimmu.2024.1385501

16 Dobson, R. et al. Anti-CD20 therapies in pregnancy and breast feeding: a review and ABN guidelines. Pract Neurol 23, 6-14 (2023). https://doi.org:10.1136/pn-2022-003426

Add comment

Comments

Amazing post! I found the discussion about estrogen desensitization and relapse risk after delivery fascinating.

I was wondering whether hormones elevated during breastfeeding, such as prolactin or oxytocin, might interact with estrogen or immune signaling pathways in a way that could affect MS relapse susceptibility?

Great question! To be honest, I don't know much about the specific estrogen signaling pathways that lead to the protective effect, and I believe it is an active area of research as to how these hormones generate a protective effect. However, the idea that these other major hormones could modulate the immune system and interact with the estrogen pathways makes perfect sense, and I would not be surprised to learn that they have a role to play as well!

Really insightful blog, I found the point about estrogen receptor desensitization really helpful as to why relapse risk rises after delivery. It makes sense that breastfeeding hormones like prolactin and oxytocin might create a mix of both repair and activation signals, which could be why breastfeeding is protective for some but not all women. Your point on that planning a head with breastfeeding compatible MS treatment is so true, the biology is very complex.

Thank you for the kind words! The hormones induced by breastfeeding absolutely add another layer of complication. Ultimately, there are likely a mix of immune activation and suppression signals that are leading to the interesting dichotomy observed in that stage post-partum.