When MS Meets Motherhood: Facing the Nursing Challenges No One Talks About

For mothers with multiple sclerosis (MS), breastfeeding can be unexpectedly complicated. Globally, MS treatments affect up to 2 million breastfeeding women (Walton et al., 2020).

Many of the medications used, called Disease Modifying Therapies (DMTs)—haven’t been approved for use during pregnancy or breastfeeding due to limited research. What we do know is that these drugs can pass into breast milk, and the effects on babies are still unclear. Because of this uncertainty, the risk is often considered too high, and breastfeeding while on these treatments is usually not recommended (Capone et al., 2022).

It’s a tough balance for mothers who want to care for their babies while managing their own health. Have we found a way for mothers to have the best of both worlds?

Understanding Multiple Sclerosis

Multiple (MS) is an autoimmune disease where our body’s immune system mistakenly attacks myelin. Myelin is the protective coating that surrounds nerve fibers. When this happens, the communication between the brain and the rest of the body becomes disrupted, leading to a range of neurological symptoms (Comi et al., 2020).

Myelin plays a key role in helping nerve cells send signals quickly and smoothly. It’s made up of fatty acids and proteins, forming what’s called the myelin sheath. When this sheath gets damaged, those signals slow down or stop altogether, which can result in the symptoms associated with MS (National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, 2025).

MS affects women three times more than men (Coyle, 2021). Most women are diagnosed during their childbearing years, which can make managing the disease especially challenging due to lack of treatment during pregnancy and breastfeeding (World Health Organization, 2006).

Figure 1 Healthy Myelin Vs Unhealthy Myelin

How Our Environment Might Play a Role in MS

Despite advances in science, the exact cause of MS remains unknown. According to research it is likely a mix of genetics and environmental factors.

Imagine you’ve got a little plant sitting on your shelf. You water it, feed it, and give it all the love in the world — but you keep it tucked away in a dark corner, never letting it see the sun. Eventually, its leaves start to turn brown. Why? Because without sunlight, the plant can’t do what it’s designed to do — its genes aren’t being “switched on” properly.

Our bodies work in a surprisingly similar way.

Our genes shape who we are biologically — from the colour of our eyes to the texture of our hair. But the environment around us also influences how those genes behave. Stress, diet, and even how much sunlight we get can change the way our genes are expressed. This is known as epigenetics.

And that’s where vitamin D comes in — the “sunshine vitamin.” People in regions with low sunlight have higher rates of MS is likely due to Vitamin D deficiency affecting immune function (Waubant et al., 2019). The theory is that less sun means less vitamin D, and that might affect how the immune system functions.

So, if you’ve been looking for a reason to plan that sun holiday… science will have your back!

We know many of the causes of MS, so what about being able to treat it?

The various causes of MS– such as environmental factors- makes it difficult to find one single cure for all patients. But what if we could reset our immune system to behave how it did before symptoms occurred?

Epigenetics doesn’t just apply to plants—it affects us too. As we age, certain genes switch on or off, revealing a cell’s “biological age,” which can differ from our chronological age. One key marker is DNA methylation, a pattern that changes over time. Interestingly, some people look younger because their cells are younger. A fascinating Stanford study explored reversing this process by reprogramming cells with six factors over four days. The results showed DNA methylation patterns up to 3 years younger in skin cells and 7.5 years younger in blood cells (Sarkar et al., 2020).

So, we can make our cells younger, how does this relate to MS?

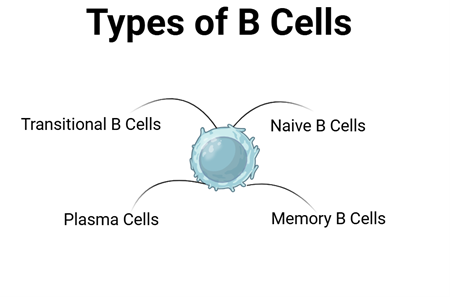

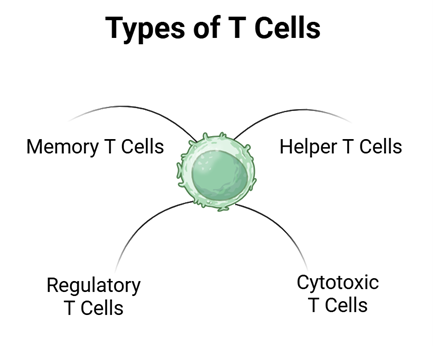

MS can affect people without the usual risk genes. It’s more about how genes behave. Since MS involves the immune system attacking our body’s nerves, let’s try making the immune cells act younger using the Stanford method to reset their behaviour. In theory this should reverse the age of our immune cells to a time where the patient wasn’t experiencing MS symptoms. Our immune system is made up of several different cells which can be separated into 2 categories; T-cells and B-cells, there are several subsets within these categories, but for ease of explanation we will use the umbrella terms.

Figure 2 Different Types of T and B Cells with their Different Functions

The proposed method of treatment

The method is to collect a patient’s immune cells – T and B cells – from blood and spinal fluid (Hrastelj et al., 2021). These cells are then purified and put in lab dishes and treated with reprogramming factors for four days to make them act younger. Once complete, the rejuvenated cells are returned to the patient through an injection into the bloodstream. This should reset the immune system to pre-MS symptoms.

This complete overhaul of the immune response, resulting in a patient with a much more youthful immune expression, and restored immune function: back to a time when a patient did not suffer from MS. Other methods are used safely to reintroduce your own cells, including treatments for pregnant women (Snarski et al., 2013). Also, this isn’t gene editing, so it avoids the cancer risks linked to those methods.

Figure 4 Flow Diagram of iPSCs treatment for patients with MS

Looking Ahead: A New Direction for MS Treatment

Whilst MS poses unique challenges, particularly for pregnant women, emerging science offers potential solutions. By reprogramming our bodies immune cells to behave like they did before MS symptoms showed, effectively means that a patient no longer suffers from MS. We could be closer to a future where MS is not just managed, but reversed.

References

Capone, F. et al., 2022. Disease-Modifying Drugs and Breastfeeding in Multiple Sclerosis: A Narrative Literature Review. Frontiers in Neurology , Volume 13, p. 1.

Coyle, P. K., 2021. What Can We Learn from Sex Differences in MS?. Journal of Personalized Medicine, 11(10), p. 1006.

Hardmeier M, W. S. F. P. e. a., 2003. Atrophy Is Detectable Within a 3-Month Period in Untreated Patients With Active Relapsing Remitting Multiple Sclerosis. Arch Neurol, 60(12), pp. 1736-1739.

Hrastelj, J., Andrews, R., Loveless, S., Morgan, J., Bishop, S.M., Bray, N.J., Williams, N.M. & Robertson, N.P., 2021. CSF-resident CD4+ T-cells display a distinct gene expression profile with relevance to immune surveillance and multiple sclerosis. Brain Communications, 3(3), fcab155. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1093/braincomms/fcab155.

National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke, 2025. Multiple Sclerosis. [Online]

Available at: https://www.ninds.nih.gov/health-information/disorders/multiple-sclerosis

[Accessed 7 October 2025].

Sarker et al. blood and skin cells youthful

Sarkar, T.J., Quarta, M., Mukherjee, S., Colville, A., Paine, P., Doan, L., Tran, C.M., Chu, C.R., Horvath, S., Qi, L.S., Bhutani, N., Rando, T.A. and Sebastiano, V., 2020. Transient non-integrative expression of nuclear reprogramming factors promotes multifaceted amelioration of aging in human cells. Nature Communications, 11(1), p.1545. https://doi.org/10.1038/s41467-020-15174-3

Snarski, E., Snowden, J.A., Badoglio, M., Carlson, K., Burman, J., Oliveira, M.C., Moore, J., Tan, J., Rovira, M., Clark, R.E., Saiz, A., Hadj Khelifa, S., Crescimanno, A., Laing, L., Musso, M., Martin, T. & Farge, D., 2013. Outcome Of Pregnancy After Autologous Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation (AHSCT) For Autoimmune Diseases (AD): A Retrospective Study Of The EBMT Autoimmune Diseases Working Party (ADWP). Blood, 122(21), p.4640. Available at: https://doi.org/10.1182/blood.V122.21.4640.4640.

Walton, C., King, R. & Baneke, P., 2020. Rising prevalence of multiple sclerosis worldwide: Insights from the Atlas of MS, third edition. Multiple Sclerosis Journal , 26(14), pp. 1816 - 1821.

Waubant, E. et al., 2019. Environmental and genetic risk factors for MS: an integrated review. ANNALS of Clinical and Translational Neurology , 6(9), pp. 1905 - 1922.

World Health Organization , 2006. NEUROLOGICAL DISORDERS: A PUBLIC HEALTH APPROACH. Neurological Disorders Public Health Challenges , 1(1), pp. 88 - 89.

Add comment

Comments

I think this is a really creative and ambitious idea and it’s interesting to see the concept of rejuvenating immune cells applied to MS. It seems theoretically plausible based on the Stanford study and existing reprogramming techniques. My main questions are about feasibility like how long would these cells last, and would multiple treatments be required over time? Also, how could this be scaled up, as I imagine personalized cell therapies could be very costly. I think these feasibility hurdles would need to be addressed before we will see these treatments availabe to general patients

Hi Jack, thank you for your comment- I believe all your questions are highly relevant and I am glad you could envision this method as plausible. Unfortunately, there have been no direct studies on applying these rejuvenation (Yamanaka) factors on immune cells, therefore it is difficult to give a concrete answer. From the research cited in the blog, the timeline for these treatments were measured in years so the hope would be the treatment would last a similar duration. For repeated treatments, so far there have only been repeated Yamanaka factor treatments applied to progenitor cells such as stem cells and fibroblasts which showed very impressive results (Rose, 2023). Although, there have been no studies done on fully differentiated cells so it would not be correct as of yet to promise this technique as a viable option for repeated treatments. Because of this, we felt it was wrong to exaggerate the capabilities of this treatment because the research simply has not been completed yet, only time will tell. You are right it would be costly, the aim is that it would be significantly less frequent than existing treatments and our approach was to cure MS from the root cause, rather than managing symptoms, for which there are many existing options. In terms of scale, there has been an exciting use of a viral delivery method for in vivo application (Cano Macip et al., 2023). We would love to have suggested this method, however explaining the development of this to target our many immune cells proved too challenging. In my opinion, it would be unrealistic to use this approach by developing several highly specific viral vectors all targeting our various immune cells, however that is not to dismiss the possibility of new publishments proving my statement incorrect. It may become a much more feasible option in the future; though with many drug targets there is an increased chance of risk. I hope I have answered all your questions.

Kind regards,

Scott

References

Rose, S. (2023) ‘Yamanaka Factors and Cellular Reprogramming’, Lifespan.io. Available at: https://www.lifespan.io/topic/yamanaka-factors/ (Accessed: 11 November 2025)

AAV-mediated delivery of OSK has been shown to reverse epigenetic aging in human keratinocytes (Cano Macip et al., 2023).

My apologies Jack, i did not cite the second reference correctly. Please see below for the correct reference to the study on using a viral delivery method of the Yamanaka factors.

Cano Macip, C., Hasan, R., Hoznek, V., Kim, J., Metzger, L.E., Sethna, S. & Davidsohn, N. (2023) Gene therapy-mediated partial reprogramming extends lifespan and reverses age-related changes in aged mice. Cellular Reprogramming. Available at: https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2023.01.04.522507v1.full.pdf [Accessed 12 November 2025].

I really enjoyed reading this blog and found your proposed method of treatment very interesting. My question is just on the safety aspect, once the rejuvenated cells are returned into the bloodstream. What safety precautions would be required to guarantee that these rejuvenated cells do not transfer into the breast milk or pose any potential risk to the infant?

Hi Biana, I am glad you enjoyed the blog! Safety of the baby and mother was 100% the main focus when discussing this possible treatment. In a clinical trial setting, the breastmilk would be constantly monitored to ensure there is no cell transfer. Also that the rejuvenated cells stay within the lymphoid tissue and does not enter the breast tissue. These would be have to be tested continuously while also pausing on breastfeeding the baby until all evidence of it is clear. I hope this answers your question!